For Allyson Allred, the past few weeks have been full of both good news and bad.

Late last month, CBS News' "CBS This Morning" ran a segment on Allred's battle with ocular melanoma, a rare form of eye cancer with no known cause that affects about five in 1 million people. A spotlight has finally been shone on what she and two of her closest friends have been going through for more than 15 years.

It's a rare cancer, but it also surfaced in two of Allred's close friends from college at Auburn, Juleigh Green and Ashley McCrary.

Now, the women say they have found at least 32 other people who went to or worked on Auburn's campus and have since been diagnosed with

On Monday, there were 15 confirmed cases linked to Auburn, said Justin George, director of cancer epidemiology at the Alabama Department of Public Health.

By Thursday, at least 20 of the suspected cases were formally verified by the Alabama Statewide Cancer Registry at the Department of Public Health in Montgomery, and the department is working to confirm 12 remaining suspected cases, McCrary said.

The good news, Allred says, is that people are finally paying attention, thanks in large part to the national news reports that aired earlier this month.

The bad news, however, is that the spotlight is starting to dim. And the number of people who say they have been affected by the disease is growing rapidly and at a rate that appears to be grossly disproportional to Auburn's population.

On a more personal level, Allred's cancer has spread to her brain, where in late April doctors found a malignant tumor. The metastasis to her brain isn't the first time deadly cancer has leaped across her body.

Allred was first diagnosed with ocular melanoma in 2001. Her doctors at that time found a 10-millimeter tumor growing in her eye — one too big to treat with radiation.

So doctors removed one of her eyes.

Continue reading below...

After the procedure, she was cancer-free for about seven years, until 2008, when cancer returned to her liver, a common progression for victims of the deadly disease.

“We’re just biding our time now. There’s not a cure for this," Allred said. "There’s not really even a treatment. We’re just trying different options to prolong our lives until there is a cure.”

Doctors were able to ablate cancer from her liver in 2008, but it returned five years later. That time, a part of her liver had to be resected, but a year later, it returned, scattered across her liver.

It was inoperable.

But doctors at Jefferson University Hospitals in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, began using a novel immunotherapy treatment applied directly into the veins supplying blood to her liver.

That therapy, developed at the hospital by some of the best experts on ocular melanoma in the country, was at least partially successful, and she's been on a break from that treatment for a year now.

But since 2014, she's had recurrences in her ovaries, which were removed, and twice in her breasts, which required her to undergo two lumpectomies. More recently, doctors found four new spots in or around her adrenal gland, kidney, diaphragm

“I really, actually believe that the Lord has already healed me," Allred said. "I just feel like he has healed me all this time, for 17 years, and I believe that he will continue to do that.”

The prognosis isn't promising

But the prognosis for those affected by ocular melanoma is not promising, and those diagnosed with the cancer often do not live as long as Allred, said Dr. John Mason, Alabama's only ocular oncologist.

"This cancer occurs in about 2,000 people in our country a year, so between five and six people out of 1 million people," Mason said, "For ocular melanoma, the outlook is that there’s up to a 50 percent chance of the cancer spreading to the patient’s liver and the patient dying."

According to the American Cancer Society, when the cancer stays in the eye, the five-year survival rate is about 80 percent.

But when the cancer metastasizes to other parts of their body the rate of survival is less than 5 percent, Mason said. And it has proven itself deadly in Auburn.

Mark McWilliams, a Birmingham architect who graduated from Auburn in 1994, was diagnosed with ocular melanoma in 2011 and later died from the cancer in 2014.

With more and more cases being verified and traced back to the University, Mason said it is time for people to start paying attention.

Mason, who practices in Birmingham, said he's seen and diagnosed more cases in the last two years than usual — an increase of about 20 percent, he said.

"If you have a lot of people who are diagnosed with ocular melanoma, which is a rare disease, in one area of the state, then we need to investigate that area of the state to find out one way or the other whether it’s environment or genetic," Mason said.

But for any research to start, they need money. And so far, despite all the reports and national attention, no one has stepped up to finance any research.

“It’s an absolute necessity,” Mason said.

Mason, who said he would like to be on the research team, said $100,000 to $150,000 would be needed to fund a study at Auburn, which could take up to a year-and-a-half to complete.

"We’re not sure whether this is a true cluster or not. It could be an increased random occurrence," Mason said. "To decide whether this is a cluster of cases, and if there’s an environmental cause or whether it’s just a higher random occurrence, would require a study to be done.”

Friends at Auburn

Green, McCrary and Allred weren’t just three random women who all happened to go to Auburn at the same time. They were all friends. McCrary and Green were members of Alpha Gamma Delta and Allred was a Kappa Delta. The three friends lived near one another in the Quad dorm complex and later in the Hill, where sorority chapter dorms were during their time at Auburn.

Their doctors thought it odd that all three women were diagnosed with the same rare cancer. Green, who was diagnosed a year-and-a-half before Allred, was the first in the group to be diagnosed when she was pregnant with her first child.

McCrary, who still lives in Auburn, was diagnosed in 2012, 20 years after her graduation.

McCrary, who attended Auburn from 1988 to 1992, was a War Eagle Girl, worked at Foy Union and was heavily involved on campus, she said.

Continue reading below...

“I’m one of those people who is sappy about Auburn in general, and I knew we would always end up back here,” she said.

When McCrary left Auburn, she moved to Birmingham for almost 14 years. During that time, she found out that Green and Allred were both diagnosed with the same cancer.

“I remember taking both of them meals,” she said.

Continue reading below...

Ten years after Green and Allred were diagnosed, McCrary would get similar bad news.

They call her 'Sweet Eyes'

She had moved to Memphis, Tennessee, had four children and was living a happy life with her family when, during a trip to the beach, the wife of one of her friends — who had been Aubie at Auburn — noticed a spot on her right eye.

She was the only one in the initial group of three to have a visible tumor in her eye, but she didn’t have many of the other symptoms typically associated with the cancer.

“I was 42, and I had floaters, and I had a little bit of blurred vision, but I didn’t have the features that some of the other people had or the symptoms some of the other people had,” she said. “But you could see mine.”

When she returned from the beach trip, she had nearly forgotten about the spot in her eye. She wasn’t too concerned. A month had gone by, and her husband, who was an administrator for an oncology group, took her out to dinner with friends from work.

McCrary said she believes the Lord took care of her when one of the women at the dinner brought up the spot in her eye. She told McCrary to let her husband, who was a doctor, take a look.

And he did — his guidance: Go to the doctor on Monday.

She couldn’t get into an ophthalmologist that quick. They told her it would take at least two to three weeks. Instead, she decided to go to an optometrist on a corner near where she lived. The optometrist didn’t even bring up the spot during her evaluation.

After the optometrist told her what glasses she needed, McCrary decided to ask about the spot.

“I truly believe that that was the Lord at work, because she was able to get me in [to see an ophthalmologist] on Thursday,” McCrary said.

When she went to the opthamalogist, they did a quality eye exam with her eyes dilated. She went into a room for them to look at her eyes, and a resident sat down and looked at it. Then another doctor came in. And another.

“Next thing I know I had eight doctors in the room, one by one sitting down to look at my eye,” she said.

The doctor in charge said she had something so rare that some of their residents may never see it.

“He took down a sticky note and wrote Iris Melanoma,” she said, though the doctor told her not to be concerned. Iris melanoma is typically benign, he told her, and they would just measure it to be safe. Thankfully, McCrary said, he decided to refer her to an oncologist to be sure.

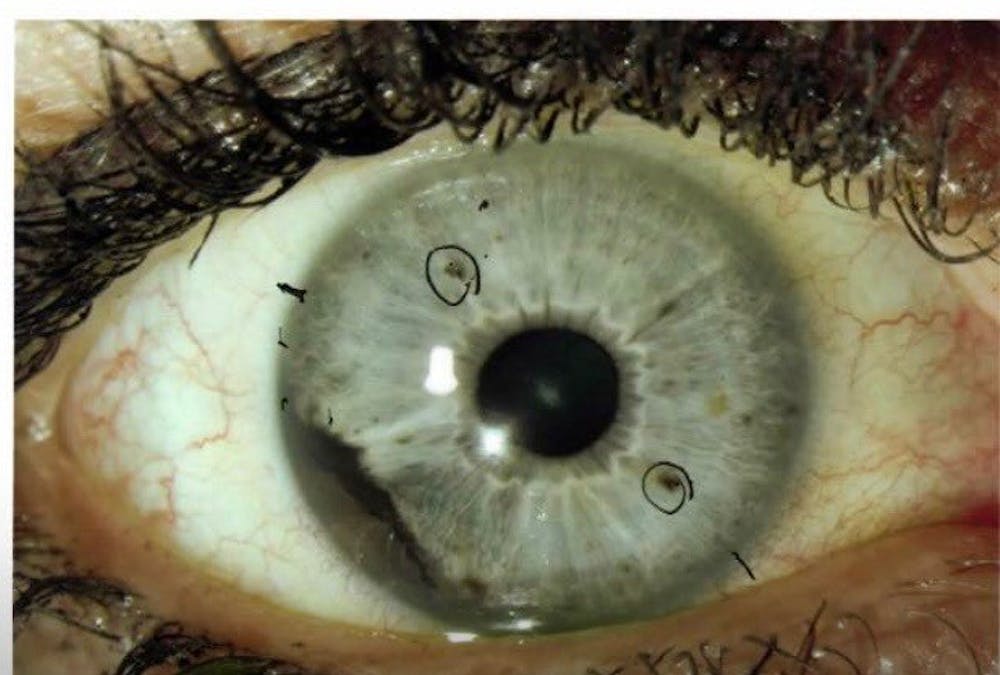

Three days later, in the ocular oncologist’s office, after running the same regiment of test, the doctor told her that the spots in her eye was not the less-dangerous iris melanoma; instead, it was a more dangerous form of ocular melanoma.

“He said it was a really bad type to have that was highly metastatic,” she said. “That’s when my heart sank. Prior to that, I just thought they were going to measure this thing on my eye and it wouldn’t be a big deal. I had no idea that the repercussions would be having my eye removed.”

McCrary’s husband called her “Sweet Eyes” ever since the two were high school sweethearts.

“This is going to sound vain, and I don’t mean it to be,” McCrary said, “but when you’re in middle school and in high school, it’s very rare to find something you like about yourself. I don’t care how pretty, how handsome or how strong you are. Most people have one thing. Maybe it’s your hair. Maybe it’s your legs. I don’t know. But for me, if you were ever to meet my daddy, he has green eyes and long eyelashes. Everybody would tell me, 'You have your daddy’s eyes. You have your daddy’s eyes.’”

Within two weeks of her diagnosis, she had lost an eye to cancer, too, just like her friend Allred.

“It changed me. I look different now,” McCrary said. “I don’t go a day without dealing with something related to this. I have no depth perception, and I fall all the time. I can be walking along on pavement, and I don’t see a step down and fall, because I can’t see that dimension. I have a hole in the side of my car because I parked too close to a menu thing at Sonic trying to get a cup of ice. If I’m in crowds of people, I don’t see people on my right side because I have no peripheral vision. I’m constantly bumping into people, and they get pissed off. It’s hard.”

The beautiful side of the story, though, is that McCrary says she doesn’t take anything for granted anymore. She realizes that no one is guaranteed a tomorrow. She doesn’t take life too seriously, and she tries to enjoy every day.

Doctors sent McCrary’s eye off for testing, and it came back positive for a Type-II tumor, which means that she had a high likelihood for metastasis.

So far, the cancer hasn’t spread. But according to her doctors, when a patient is under the age of 45, the peak of metastasis time is around the seventh year, which is when Allred’s cancer began to spread throughout her body. McCrary’s now a year out from her seventh year.

“I'm praying that my life doesn’t change on that day from bad news,” she said.

Finding more survivors, victims

McCrary’s family decided to move back to the area with the intention of staying so her second child could eventually get in-state tuition.

“I can’t help but think that was the Lord’s work, too, because if I was in Memphis, I couldn’t be as involved in what is going on here as I have been,” McCrary said.

And she has been involved. McCrary said her email and Facebook page have been flooded with messages from 42 people who said they went to Auburn or worked at Auburn and were later diagnosed with the cancer. She’s sent those people a questionnaire about their diagnosis. Some have since been ruled out, leaving 32 who self-reported that they were diagnosed with the cancer and had links to Auburn.

Continue reading below...

About 60 percent of those who self-reported were women and 40 percent were men, McCrary said, based on their questionnaire.

McCrary said nothing really links the cases together, other than they all attended or worked at Auburn for an extended period.

Most of the respondents didn't live on campus, though the three initial women did, and there is a variety of different majors and departments represented, though there was a high number of education and pharmacy majors among the women who self-reported.

According to the National Cancer Institute and the Ocular Melanoma Foundation, there is no known reason or cause for ocular melanoma, which is sometimes referred to as uveal melanoma.

Doctors from Philadelphia’s Jefferson University Hospitals traveled to Auburn in February to hold a small conference to see how many people they could find with stories similar to the three women. That’s when the numbers started jumping.

Since then, McCrary, Allred and others in the group have been searching for funding for a research study. According to Mason, the ocular oncologist, the investigation would include the Alabama Department of Public Health, a geospatial analysis and genetic analyses. Geospatial specialists and epidemiologists would search for an environmental cause at Auburn, while genetic experts, including Mason, would rule out any genetic causes.

“If a study were to find that it’s purely genetic, then unfortunately at this time, there’s not a lot we can do because we can’t alter the genetics at this time,” Mason said. "But if the study did find an environmental cause, then we could certainly modify the environmental cause, which may lead to less people getting ocular melanoma.”

State Sen. Larry Stutts, who is a practicing doctor in North Alabama, attempted to help the women get funding through Auburn’s appropriation in the Education Trust Fund, McCrary said, but the push for that funding failed. The Legislature declined to give them the funding. Since then, the University hasn’t put up any money, either.

The University is working with ADPH to review the confirmed cases along with researchers from the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson University Hospitals and the coordinator of research in North Carolina, where at least 18 patients in Huntersville were identified to have the cancer in a formal investigation.

The ADPH and the University have declined to call the cases a formal “cluster,” stating that more verification and research are needed to determine whether a common cause led to the diagnoses.

According to ADPH, a cluster is a higher-than-average number of cases in a particular area over a limited period of time.

“While we have been informed by ADPH officials that it would be premature to determine that a cancer cluster exists in the area, we are cooperating fully with their work. The health and safety of our students, employees and alumni are of the utmost importance,” the University said in a statement.

Waiting on results

McCrary said she understands why the University can’t do anything until everything is verified, though she said she would have thought University officials would have been more proactive and vigilant.

“There are people on our website saying they’re trying to decide between other schools and Auburn, and based upon this, they’re going with the other schools,” McCrary said. “And yet, the University as a whole has not done anything. And there are people who are very disappointed in that.”

“It breaks my heart, because I love Auburn,” McCrary said.

While she said the University as a whole hasn’t done anything, she said Auburn University Medical Clinic medical director Dr. Fred Kam has been working with them as the cases continue to be verified.

“He's just one person, but he is helping us,” McCrary said.

The University has given Kam the go-ahead set up meetings with researchers and doctors in North Carolina, Birmingham and Miami, and the state expects to give their verified cases to the University by the end of next week, McCrary told The Plainsman.

McCrary said it so far has been disheartening that no one has stepped up to pay for the funding — not the Legislature, not the University — but that she still has hope that someone will step in, and they soon hope to launch a way for individuals to donate that is tax deductible. Others are not as hopeful.

“When I tell you that some people are furious, something is going to come out in the next day or two, and it’s not going to be very pretty at all,” McCrary said. “We just feel that we’re going to have to take this into our own hands to raise the money."

McCrary and Allred said they were hesitant about calling for the University to fund the research itself. They worry that the public won't trust the results of a study funded by the University, which has a dog in the fight. But some members of the group of survivors would like for the University to offer funding.

Continue reading below...

When McCrary goes in for scans and testing every three months, she says world of people tell her they’re praying for her. “That is great. I want people to pray that my scans are clear,” she said. But the best course of treatment is to find something early. She tells them to, yes, pray that it’s clear, but also that if there’s something there, that the radiologists find it so they can treat it.

“I say the same thing about Auburn,” she said. “Do I want something to be there? No. I want them to find absolutely nothing. But if there is something there, I need them to find it. I have a child there. If I worked there — and several of the people worked on campus, several died from it — if I was a professor, I would be knocking on doors, saying what are you doing to ensure my safety.

“If I was a student, I would be screaming at the top of my lungs, saying, ‘Yes, it may be nothing, but I’m a little scared,’” McCrary said.

McCrary said she wants people to know they need funding, and they are disappointed that no one has offered any.

"Auburn University just raised $1.2 billion for the University. There’s a person in Auburn’s circle of people who could write a check for $100,000 to fund this research,” she said.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Chip Brownlee, senior in journalism and political science, is the editor-in-chief of The Auburn Plainsman.