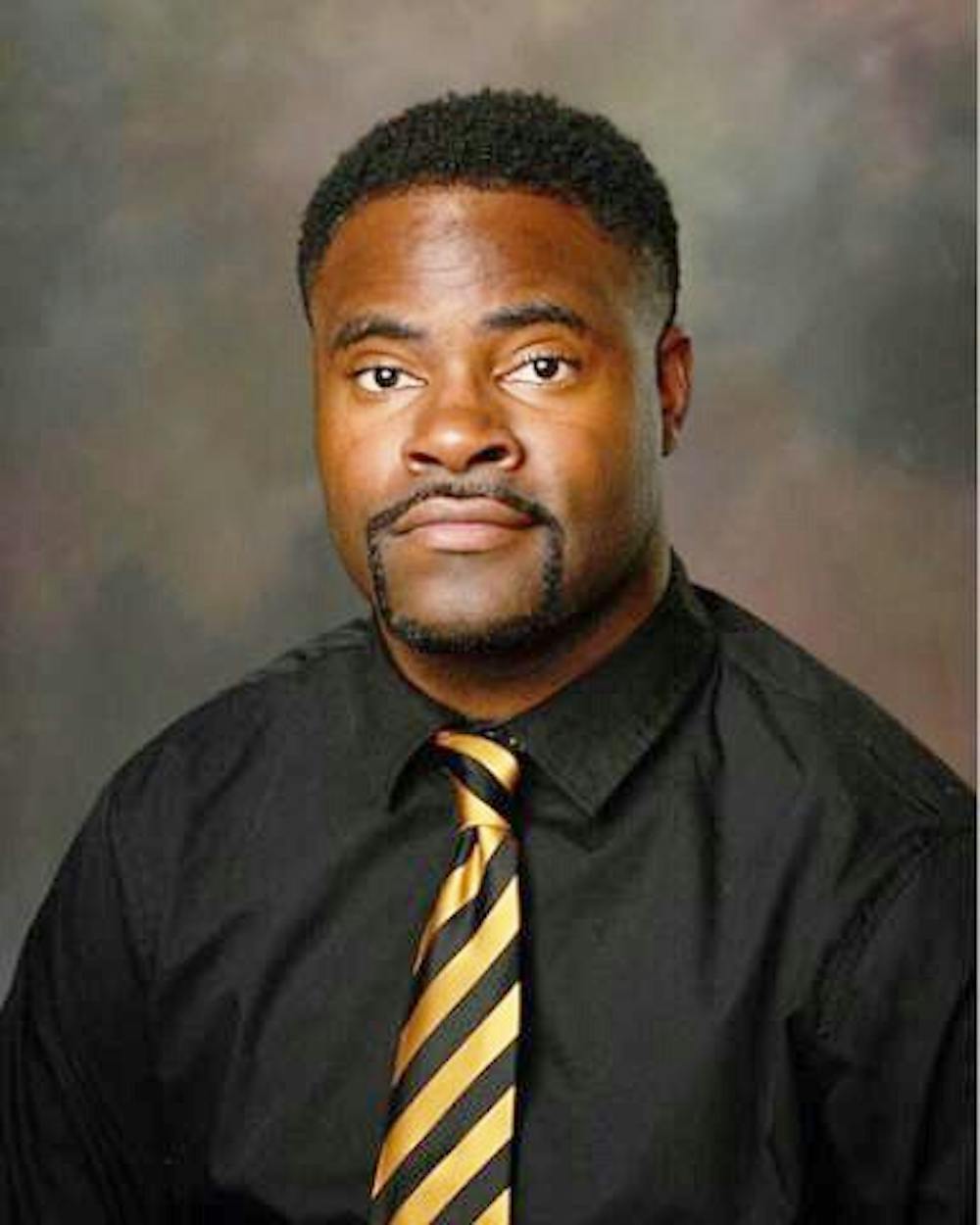

Christopher Beamon can’t believe he’s alive.

“Looking at me, the average person would think I don’t have a brain injury, or that everything’s okay,” he said. “But I’m in pain just about every day.”

Just over two years ago, Beamon, 27, was a graduate student at Auburn University, but before that, he was a young man moving up in the world.

“I joined the Army right out of high school,” Beamon said.

He was stationed in Germany and Fort Hood, Texas.

“Did four and a half years before getting medically discharged due to Type 1 diabetes and being insulin-dependent,” Beamon said.

That didn’t deter him from moving forward, as he went on to get a degree from Texas Southern University and later applied and got accepted to Auburn.

It was Aug. 10, 2017, when he received a phone call from a friend in the University’s Veterans Resource Center.

“Us military men, we’re close,” Beamon said. “[He] was expecting a baby girl, so he was looking for a bigger place. I told him I would help him move, and so I did. He was the third person I helped move that week.”

The two were driving in Beamon’s truck and turning onto Glenn Avenue, their boxes stacked in the bed, when they heard a noise from behind the vehicle. He put on his flashers and stopped to investigate.

“Something fell off of my truck, and I went to go get what had fallen off,” Beamon said. “I got hit outside of my car by an F-250 truck. Ran over. He crushed my entire right side.”

The driver collided into him at 55 mph, sending Beamon flying into the air and totaling both trucks. The veteran said in this brief and sudden sequence of events, his life was forever changed.

From that point, Beamon’s memory is sparse. His recollection of the moments after comes only from what others have told him of the incident. He was airlifted from the scene to Piedmont Columbus Regional Hospital in Columbus, Georgia, where he was sent to the intensive care unit for several weeks.

“[My sister] had told me that it didn’t look good,” Beamon said. “For a week straight, I had no brain activity. We thought that I was not going to make it.”

Beamon was in a severe coma for almost four weeks following his arrival in the hospital. His sister, Ijella Hannon, traveled from her home in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, upon hearing word of the accident.

“She was willing to give up her job and move to Alabama,” he said.

Hannon didn’t move to Alabama, and Beamon said she nearly lost her mind while dealing with the anxiety of not being there for him.

Hannon’s distance from her brother limited her visitation to weekends only.

Christopher Beamon lies in a hospital bed at Piedmont Columbus Regional Hospital a week after being admitted in Columbus, Ga.

Before the accident, Beamon had befriended Kendall Parks, a Ph.D. student in political science and fellow U.S. Army veteran, through a leadership class the previous spring.

“He was prior military, I was prior military, and when he kinda figured out what I did, he was all freaked out,” Kendall said, referring to their similar stories in service and in college. “So, we became friends, and that summer we were going to take another class together.”

In the class, a group project was assigned, and Kendall was a leader for one of the teams.

“I said, ‘I’ll do it if Chris Beamon is in my group,’” Kendall said. “[The instructor] said, ‘I’m going to do a random number generator,’ and I said, ‘OK, well do the random number enough times that Chris ends up in my group.’”

Beamon found himself working with Kendall in the end, and in the four-and-a-half-hour class, the two “spent a ton of time together and really became friends,” Kendall said. Once that semester wrapped up, Kendall celebrated with a party and invited Beamon to his home in Smiths Station, Alabama. There, Beamon also met Kendall’s wife, Debbie, a principal at a school in Fort Benning, Georgia.

“Chris told me about his background,” Debbie said. “I had only had a conversation. It was maybe like 20 minutes with him, and I was very impressed with him.”

Christopher Beamon, Debbie Parks and Kendall Parks pose for a photo at Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn, Ala.

Just days later, the accident happened, but the Parkses wouldn’t be notified for another week.

“Around [Aug.] 16, we had a meeting for my department and I came to that, and this girl came up to me,” Kendall said. “She said, ‘You’re pretty good friends with Christopher Beamon, right?’”

The student informed Kendall of Beamon’s accident, and he phoned the hospital as soon as he returned home, but he was told he wasn’t granted visitation until the next day.

Kendall requested hospital staff provide Beamon’s family with his phone number, so he could offer to open his home to them.

“Kendall went immediately to the hospital, and I was at school,” Debbie said. “He came home and told me, ‘We’ve got to take care of him.’”

Beamon was afflicted by a myriad of both physical and mental conditions that took him more than two hands to count.

He lost a year and a half of memories before August 2017 and his short-term memory.

His hip was crushed in the incident, along with the C1, C2 and C4 vertebrae in his spinal cord. The nerves in both arms are permanently damaged, leaving the left limb stuck in an “L” position, while the right doesn’t allow him to ball up a fist anymore. A bone in the left arm grew in excess, becoming almost fused with another. The skin from under his left knee down to his ankle was lost.

His head swelled up for a time, resulting in internal bleeding. An eye socket cracked, forcing him to wear specialized glasses. Further nerve damage in his lower extremities resulted in a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome.

Surgeons inserted a 14-inch rod into his right leg for support, and while hospitalized, he had to relearn how to read starting at a kindergarten level.

Doctors at Piedmont were overwhelmed with the number of injuries Beamon sustained. According to Kendall, a sign was placed on his hip as an advisory to staff. It read: “Do not roll this patient over. His hip will fall out.”

Debbie was in shock at his state after her first visit and made it a mission to be the daily caretaker Beamon needed after becoming acquainted with the grad student’s family from Louisiana.

Debbie spoke to the unconscious Beamon about ongoing news in the short time he was in a coma, not knowing if he could hear her or not. She said on one occasion, when he at last came to and acknowledged her presence, he mouthed the words “Don’t go,” as she was readying to leave.

Beamon awoke from the coma in early September and was moved to a non-emergency floor at the hospital. When word spread of Beamon’s miraculous survival, new visitors stopped by.

“The governor [of Alabama, Kay Ivey,] came to visit me along with elected State Auditor Jim Zeigler,” Beamon said. “The auditor’s office notified [Ivey] about it, and they had 70 to 80 others from the state [government] come and see me.”

Beamon had interned at the state capitol a few doors down from Ivey’s office, and she recognized his name upon learning of his status.

“She would see me with my jacket pullover and say, ‘War Eagle,’” Beamon remembered with a smile. “Every morning when she would come down the hallway, it would be, ‘War Eagle, young man.’”

Things took a turn for the worse, however, as the traumatic brain injury intensified.

Two months passed, and he was transferred to a TBI unit in New Orleans.

“With a brain injury, it turned me very combative,” Beamon said. “There were some moments where I thought people were playing tricks on me.”

The stay at the New Orleans unit saw Beamon fight through some of his darkest days as a medical patient. His clouded mind in the seven weeks he was kept there led him to believe he was in a clinical trial setting, and he was confused each time he awoke and found himself in a hospital.

Debbie said she remembers Beamon when his memory and thoughts were hindered in October 2017.

“He was even worse than he had been here,” she said. “He told me later he thought he was being imprisoned in some way, and he couldn’t get out. When he saw me, he thought I was coming to set him free, and then I didn’t.”

Debbie said she couldn’t stand to see the state Beamon was in.

“I started wondering at that point [if we were] going to get the old [Beamon] back ever,” she said. “I was talking to my school nurse and asking [if it was] a permanent thing. She said, ‘Sometimes it is, sometimes it’s not.’”

The TBI facility released Beamon around a month after he was admitted in late September, despite the fact that his health was regressing, Debbie said.

Beamon was sent back home and looked after by family members and home care nurses.

Meanwhile, Debbie continued attempts to keep in touch through letters and eventually received an unexpected call sometime in November. It was Beamon.

Christopher Beamon, Debbie Parks and Kendall Parks pose for a photo on Hitchcock Field in Auburn, Ala.

“He started telling me about this dream he had where he was in a car accident, and I was there, and I took care of him in the hospital and on and on and on,” she recounted. “He said, ‘I don’t think it’s a dream.’ I said, ‘No Chris, it wasn’t a dream, it all happened.’”

Some of the most demanding recovery came with Beamon’s occupational, speech and physical therapy prior to his return to Auburn. He was more than ready to get back on his feet, sometimes to a dangerous extent.

“[The nurses] said, ‘Don’t get out of the bed, you can’t walk,’ and I didn’t know,” Beamon said. “I didn’t even recall I was in an accident. I thought I could walk to the bathroom, so I unplugged all the machines. I tried, and I remember me falling.”

The rehabilitation process was a three-month long ordeal and required Beamon to be restrained in actions such as feeding himself, writing his name and relearning words and mathematics.

“It was just small words,” he said. “I can remember I didn’t know what words like ‘display’ would mean or words like ‘demonstrate.’ It was learning how to do three times two plus two. It was the same things we learned in grade school.”

As 2017 was coming to a close, Beamon was able to move on to outpatient therapy having visited several different clinics.

He had regained the ability to drive a car, and that was more than enough motivation for him to get back to Auburn, though his family wasn’t so eager.

“They wanted me to stay and go to LSU,” he said. “LSU is a pretty good school — they even have my program. But if I can’t go back to Auburn, I thought, then I’m not going back to get my master’s, period.”

They relented by May, and thanks to the aid of the University’s Veterans Resource Center, he was able to enroll back in Auburn.

Upon his return, the Parkses offered to throw a welcome-back party for Beamon, and he invited his guardian angels — the nurses who saved him.

“Very quickly, he said, ‘I want to invite my ICU nurses,’” Kendall said. “He wanted to honor those who had helped him.”

The Parkses were especially relieved to see him back in town, but more than that, they wanted to see him back in school.

In November 2018, Beamon got to experience the moment of a lifetime. He was recognized in Jordan-Hare Stadium as honorary team captain on Military Appreciation Day.

Beamon enrolled in classes in Spring 2019, eventually receiving the Robert S. Montjoy Outstanding MPA Student Award.

Nowadays, Beamon isn’t flawless in his mobility, but he can move on his own without the assistance of others, a drastic change from even a year ago.

He often uses a scooter for transport between his night classes.

“Bending certain ways is a no-go,” Beamon said. “There’s a struggle with putting on my socks every morning because the leg with a rod doesn’t bend. There’s a struggle with walking up and down the stairs.”

Nevertheless, he still has additional goals he wants to see come to fruition.

With the Iron Bowl set in Auburn this November, Beamon would like to take part in the festivities before the game.

“The veterans are marching 150 miles from Tuscaloosa to Auburn to present the gameday football,” he said. “I know that I won’t be able to participate the whole 150 miles, but I would like to be able to help wherever I can, whether it’s helping with supplies or on the road marching.”

For now, Beamon is more than satisfied to be on campus taking his final semester.

He retains a keepsake book of about 200 orange and blue pages with signed notes from hospital guests, as well as a memory box filled with cards.

“The accident was just one small segment of the life that I’ve lived,” Beamon said. “I’ve stayed positive the whole time. I haven’t lived out my dreams yet.”

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.