Aniah Blanchard was last seen on Oct. 23, 2019, before her death.

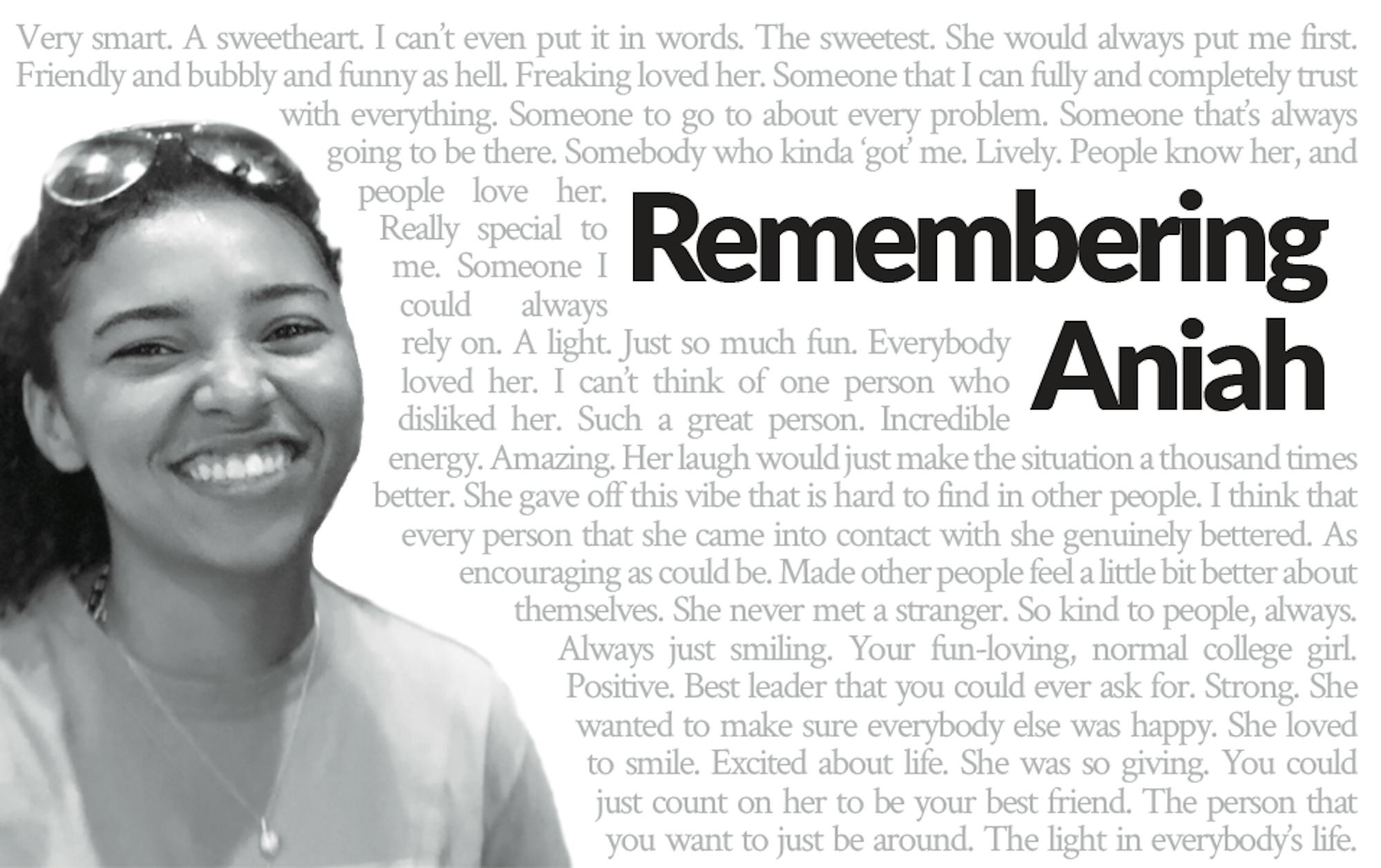

She was 19, a second-year student at Southern Union State Community College with hopes of becoming an elementary school teacher one day. She was a daughter, a sister and a friend; she was an athlete; she was an artist; she was funny and smart and kind; she was loving; she was loved; she was — “I can’t even put it in words.”

I. Remembering Aniah

Aniah was born on June 22, 2000. Her older brother Elijah, senior in supply chain management at Auburn University, remembers all the time he spent growing up with Aniah. The two were inseparable.

“We were all each other had,” he said.

And they would fight and argue, like siblings do, but there was always love.

Her family has memories of her, stories — there were always stories — like when she was just four or five years old, and her mother would take her to her grandmother’s restaurant. Aniah would help out, “working, working, working.” She was always a hard worker, her mother Angela Harris said, ever since she was just a little kid, and she was always friendly.

“She always greeted everyone with that little giggle laugh and smile,” Harris said.

It was always everyone. There was no one that she did not meet with a smile, her friends and family said.

“She never met a stranger, you know,” said Hannah Crocker. “She would just be so kind to people, always.”

Aniah was one of the first friends Crocker had. The two first met in sixth grade at Homewood Middle School, and they’d spend their classes talking to each other. In eighth grade, they played softball together. By then, they’d begun talking every day, and they spent every Thanksgiving, Christmas and spring break with each other.

“We were always together,” Crocker said. “I mean, literally, inseparable.”

Their friendship was special. But the people who were friends with Aniah often spoke about her the same way. Like Naomi Taylor, who met Aniah in fifth grade, who said that Aniah “was somebody who kinda got me.” Taylor and Aniah were some of the only biracial students in their grade, and that was part of what helped them grow so close.

Taylor remembers stories of middle-school drama, but it was never anything that broke their bond.

“She was a lot like a sister,” Taylor said. “In middle school — it’s so stupid — we would argue and then not talk for a few days, and then as something crazy would happen, we would just be right back to being friends like nothing happened.”

Aniah’s friendships with Crocker and Taylor continued throughout the years and into high school. Aniah continued playing softball, and in her senior year she was named the captain of the team.

“When I say just the most positive and best leader that you could ever ask for — she just amazed me with the leadership quality,” Harris said. “The positive energy she brought her team was amazing.”

She was voted by her teammates as the Patriot Award Winner her senior year, which is given to one student athlete who exhibits “exemplary character on and off of the field, leadership skills to promote a team mentality and a true passion for others and their success,” according to Homewood Athletics’ website.

“Aniah is one of those student athletes I wish I could have kept on my team forever,” her coach Tifanny Statum wrote on the Homewood Athletics website. “As a teammate, Aniah had a way of making the best of every situation with her laugh. Till this day I can close my eyes and hear her.”

She had other interests, too. She loved to paint and draw, and Harris has kept her artwork from over the years.

“You have to see the artwork I have since she was a little girl,” Harris, her mother, said. “I have tons of artwork, and it’s so beautiful. And I’m so glad that I always kept all that.”

Throughout senior year, Aniah continued drawing. And when it came time for college, she decided to go to Southern Union, just down the road from Auburn where Elijah was completing his freshman year.

“I was real surprised when she even followed me to Auburn, ‘cause she wasn’t even an Auburn fan, and she didn’t seem like she wanted to even follow me down here,” he said.

That was when Elijah, her brother, said they became best friends, even closer than when they were growing up. They would hang out, introduce each other to their friends, eat — “We like to eat a lot,” Elijah joked.

“We just hung out,” he said. “She didn’t have anything to do, I didn’t have anything to do, we’d just hang out and watch shows.”

Around this time, Aniah met Sarah O’Brien, another Southern Union student, who was in the same math class as her.

“I thought she was snooty,” O’Brien said with a laugh. “She was very smart, and literally I walked up to her because I wasn’t understanding what we were learning that day in class, and I was like, ‘Hey, you seem to understand this, do you mind meeting up after class or something and just studying with me?’”

Their friendship started off more as tutoring, O’Brien said. But after O’Brien realized that the first impression she had of Aniah — a “snooty” girl from math class — was wrong, the two really hit it off.

“I don’t know, I can’t even put it in words, like she was just the sweetest, and she didn’t care; she would always put me first,” O’Brien said. “She was just friendly and bubbly and funny as hell.”

They signed a lease together for an apartment at Evergreen for their second year. They hung out together and with Elijah and O’Brien’s sister. O’Brien said Aniah was someone she could fully and completely trust. She could talk about anything, and Aniah would always listen.

“She doesn’t care how many times I cry to her about the same boy; she’d sit there and let me cry more,” O’Brien said. “You know, someone that’s always going to be there.”

Throughout those two years at Southern Union, Aniah and Crocker still talked every day, sending texts and calls between Auburn and Tuscaloosa, where Crocker was enrolled at Shelton State Community College. There wasn’t a day that went by where the two didn’t know what the other was doing.

On Oct. 23, 2019, Crocker went in at 6 p.m. for a night shift at DCH Regional Medical Center — she had wanted to be a nurse at the time — and sent a message to Aniah at about 7:30 when she got a chance during work. Aniah had gone to a funeral that day, and she wanted to check on her. Crocker said that the funeral had made Aniah upset, but it seemed like she would be fine. The two kept sending Snapchat messages to each other periodically through the night.

“And the last Snapchat that she sent was somewhere between nine and 11 that I got, and she’s just like, ‘I miss you so much, I really wish that you were in the Auburn area,’ and stuff like that,” Crocker said. “And I had responded being like, ‘Yeah, of course, I miss you … you know, I can’t wait to see you,’ because … she was supposed to come over to my house Oct. 26 … I Snapchatted her, and by the time I sent it to her, of course it was late, I was working night shift, and it wasn’t uncommon that she did not respond, because that’s so late, like that’s fine. But, of course, the next morning I get woken up by dozens of calls. And I was like, ‘What is going on? You know, this is being woken up at midnight. What is going on?’ But, yeah, who knew that that’s gonna be the last time you’re talking to somebody.”

II. Grief

Aniah’s kidnapping and murder sent a tremor throughout the country as nationwide news outlets reported on her loss, and her death lit the spark on the push for legislative bail reform. The case shook the ground on which members of the Auburn community stood, as fears of future kidnappings loomed large in the months following. The community reeled from the loss of an innocent woman, and loved ones reeled from the loss of a friend, sister, daughter.

For those who were close to Aniah, the grief was so acute it felt at times like it was almost too much to bear. The past week, one year since her loss, has amplified those feelings that they are still dealing with. For some, all they can do is cry.

“I’ve actually just been sitting in my bed crying this morning,” her mom said. “My heart’s broken. I miss her so bad. And it’s hard to even want to, it’s hard to even want to live. That’s just the way it is. That’s how I feel; I hate to say that but that’s how it is. I don’t want to live without her.”

Harris has tried to keep some sense of normalcy at home for Aniah’s other 14-year-old brother and 7-year-old sister. She doesn’t want every day to be another day of grieving, but after losing a daughter who was a best friend, those profound feelings of sadness are anything but gone.

The pain is unbearable for everyone close to Aniah, Harris said.

Everything just feels a lot dimmer, now, Taylor said.

For Elijah, it doesn’t feel real.

“Like, I think about calling her all the time, and I have to be like, ‘Wow, I know I can’t do that anymore,’” he said. “And like it still doesn’t even click in my head that I can’t do it.”

Crocker finds herself doing the same thing. She’ll wake up some days and decide to give her a call and tell her about something before it sinks in.

“Oh yeah, I forgot,” Crocker said. “Okay, never mind.”

In the time shortly after Aniah’s death, O’Brien said the grief worsened her anxiety to the point that it interfered with normal tasks.

“I had so many anxiety attacks, like even leaving my house; there was no way I was able to focus on school to the best of my ability,” she said. “I just needed some time to grieve.”

She moved back home to Andalusia, Alabama. She shut down, took time off from school and stayed in the house.

“It go so bad to where, I mean it was either kill myself or go to therapy,” she said. “So I started going to therapy, and everything has been better since then, so thank God for that.”

O’Brien got a support dog to help with her anxiety and continues going to therapy. She’s since moved back out of her mom’s house, with a friend in Andalusia. But that move, and the harsh reality of Aniah’s kidnapping, still keeps her anxiety high.

“I’m constantly looking over my shoulder,” she said.

Everyone who loved Aniah has moved through the past year differently. Everyone has felt the pain differently; everyone has found a different way to manage. Things are not the same. And it takes a lot out of you, Crocker said, to “wake up and produce your own life.”

“You start going through the motions, and you’re like, oh my goodness, this is harder than I thought,” Crocker said.

Elijah said that he had to start working out and stay busy with schoolwork and a job at a gym to try to bring things back to normal. Others found comfort in different ways, like time with friends.

O’Brien talks with Elijah nearly every day and goes back up to Auburn pretty often to see him and Aniah’s dog Blue that he cares for now. Crocker and O’Brien both talk with Harris almost daily because she’s someone who understands the pain they’re feeling, Harris said. And Harris said that the outpouring of support from the community has been incredible.

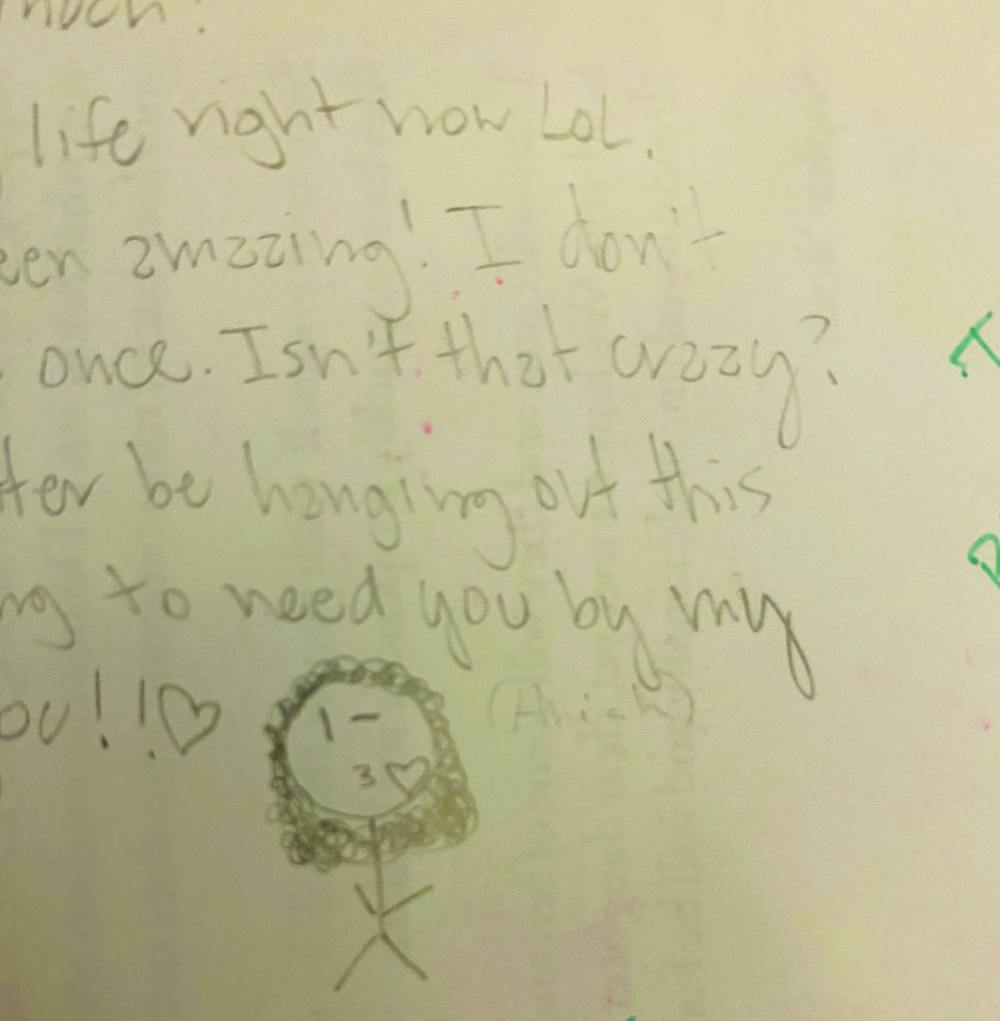

There’s a drawing in one of Taylor’s high school yearbooks, a stick figure girl with curly hair, winking and blowing a heart; there’s a message next to it, and Aniah’s name signed right beside. Taylor got the drawing tattooed on her arm to remember Aniah, hoping it would make her feel better.

“It was really cute, and personal, and I look at it, and I don’t know if it’s her or me, I’m guessing it’s her, that she drew the stick figure of, because it has curly hair — we both have curly hair so it’s kind of hard to tell,” Taylor said. “But it just brings back memories. Good ones. I don’t have any bad ones.”

It’s also been an echo of the loss that she’s felt.

“It’s just a constant reminder, also,” she said. “I’m never gonna forget her, that’s for sure. So I think only time can help me.”

The next part of this series will be in the Nov. 5 edition of The Plainsman.

Share and discuss “Remembering Aniah” on social media.