Next time you turn on your favorite song, thank Opelika for making quality recordings possible and affordable.

Most people don’t know that the first magnetic recording tape in America (“Irish” brand) was produced in Opelika, and that one of two original magnetic recording machines of such a venerated creation (the other being housed in the Smithsonian Museum) is now stored in a former auto parts store on Ninth Street.

Opelika’s Museum of East Alabama has embraced its word-of-mouth reputation and relies on goodwill and street traffic to find the building, nestled just a shout from the county courthouse and a stumble from the popular Irish Bred Pub.

Glenn Buxton, executive director of the museum since 2005, has spent nearly his whole career selling the “intangible” as the manger and consultant of several radio stations throughout the Southeast and Alabama prior to becoming executive director.

“If you can sell radio air time, something that’s completely intangible, you can sell anything,” Buxton said.

While many people may think of the past as escaping physical reach, once inside the museum it’s apparent that there is no shortage of historical items.

“Now we’re to a point where we have to be very selective in what we preserve,” Buxton said. “There’s just not any place to store it all.”

With more than 5,000 items and plenty of excess in storage, the term “selective” might seem to visitors like an understatement.

Buxton, 70, calls himself “semi-retired” and has no background as a historian, just a passion to enrich and enlighten his community.

“If somebody would have told me in 2000 that I’d be doing this today, I would have mostly certainly said ‘you’re crazy,’” Buxton said.

Buxton, who could pass for an aged Johnny Cash, wears a plaid button-down shirt and raises his salt-and-pepper eyebrows as he delves into the history of the museum.

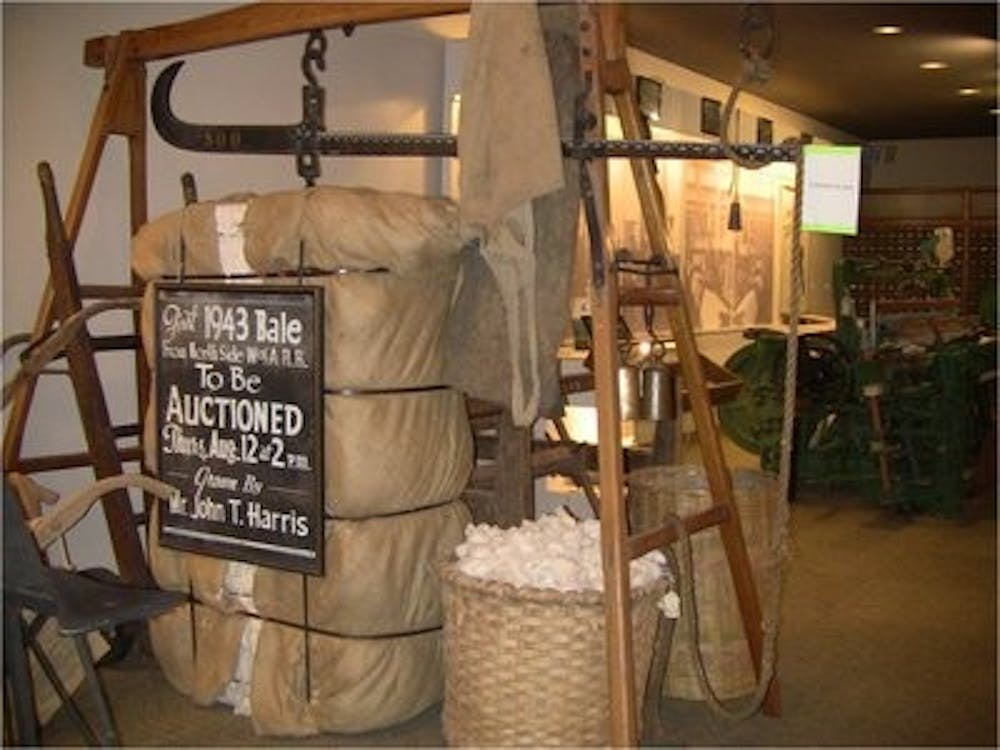

The Museum of East Alabama opened in 1989, founded by Eleanor and John T. Harris with financial help from celebrated former Auburn baseball player Billy Hitchcock.

The Harrises had previous experience opening a museum in Eleanor’s hometown of McCook, Neb., before founding the Museum of East Alabama in John’s native Opelika.

Everything in the museum is donated, with a strictly informal policy of not purchasing items, meaning that the exhibits are comprised entirely from the good will and concern of others.

Jim Hardin, president of the board of directors for the museum, is proud of the “no-purchase” policy.

“Everything in here’s got its own little story,” Hardin said. “Each item used to belong to a person or organization.”

There are six exhibits, all recently constructed from the 2010 $100,000 renovation that occurred in partnership with Auburn University’s industrial design program.

The museum’s exhibits are divided by section: East Alabama at Home, at Work, at War, on the Go, at Play and The People of East Alabama.

Before the renovation, Buxton explained that there was no real organization for the items contained within.

“If you would’ve come in here four years ago, it looked more like a thrift shop than a museum,” Buxton said.

Visitors should be advised that walking through the six exhibits can take some time because of the sheer amount of information presented and overall skilled organization to utilize all available space.

The first exhibit, East Alabama at Work, contains items from the agricultural, technological and construction industries that have developed in the area, including the first magnetic tape recorder in America (taken from Nazi Germany by John Herbert Orr), the origins of Ampex and “Irish” brand recording tape, a cotton scale from the early 1900s, antiquated medical equipment from the founding of East Alabama Medical Center and a loom from the Pepperell Mill.

Next, East Alabama at War showcases military uniforms from Desert Storm to the Korean War, along with an exhibit about World War II German POW camp, Camp Opelika.

“Most people don’t know that we had a POW Camp that held more than 3,000 Germans,” Buxton said. “It was probably the best treatment POWS anywhere got. The camp had its own track team and theater, a lot of interesting stuff.”

Continuing the tour, East Alabama on the Go shows how transportation in the area has changed over the years and contains the first item ever donated to the museum, as seen on its logo, a restored carriage from 1920.

Stepping into the new renovated annex, East Alabama at Play contains leisure items from Alabamians and boasts a jersey from Auburn legends such as Bo Jackson, baseball player Billy Hitchcock and the world’s largest collection of Roanoke Dolls (from Roanoke, Randolph County) along with other toys, games and books.

The final exhibit, People of East Alabama, shows visitors items from Alabama’s Creek Indian heritage and wares constructed by residents of the area. Within this exhibit, a dugout canoe estimated to be 5,000 years old sits in glass next to mill stones and a leather costume from when Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show came to Opelika.

While not heavily advertised, the museum allows visitors to touch and carefully observe everything in the exhibits as long as they demonstrate respect for the preservation of the items.

“Just about the only time that I tell people not to touch anything is when we have groups of schoolchildren in here,” Buxton said. “Then I say ‘don’t touch anything unless I say so!’”

Hardin agreed with Buxton’s policy on being watchful with small children, but would like to see more school groups pass through.

“We’re always looking to get field trips in here,” Hardin said. “It won’t cost them anything, so it’s an easy way to educate kids.”

Hardin thinks many locals overlook the museum without giving it much thought, because of its presence and lack of formal promotion.

“It’s the ‘backyard effect,’” Hardin said. “If you live in Paris, there’s nothing special about seeing the Eiffel Tower.”

Buxton and Hardin estimated that half of the visitors to the museum are from abroad, as evidenced by the welcome sign that has greetings in Japanese, Portuguese, Finnish and Icelandic, among others.

“Whenever somebody comes in from a different country, we tell ‘em to write a greeting in their language,” Buxton said. “They know it best, I couldn’t write it.”

The museum gets help from mostly student volunteers, largely Auburn University anthropology majors, who come in whenever their schedule allows to help Buxton with the day-to-day operations.

Callie McManus, senior in anthropology, started working at MEA last spring when her friend and fellow museum co-worker, Stephanie Canington, said that the museum needed help.

So far, McManus said it has been nothing but a great experience.

“I work with digital archiving and updating our database at the museum,” McManus said. “It’s been fun, it’s been interesting. You don’t get to think about history much these days. To hold a newspaper from 1873… it’s something that most people don’t get to do each day.”

One of McManus’ favorite aspects about the museum is its consistent influx of donated, often hyper-localized, items.

“The people that donate these items, they’re not strangers,” McManus said. “These are our neighbors and friends, sometimes down the street. To have that in a museum is really neat.”

Wei Beach, a self-employed graphic artist from New Orleans, helps Buxton out from time to time with placing advertisements, updating the newsletter and archiving.

“It’s such a cool place,” Beach said. “You think about small towns not having much history, but there’s so much in such a little place. We don’t have room to store it all.”

Beach thinks that the museum’s presence in the community is one that should be an example across the United States.

“They have almost 6,000 pieces,” Beach said. “Every time I’m in there, somebody comes in to donate something. In such a small town, I still find that amazing.”

Despite the ever-present lack of space, the museum continues to receive donations and store them in its attic and a storage facility across town.

Some items in storage, such as two fire trucks donated by the City of Opelika and the multitude of typewriters, Buxton and Hardin hope to make sure become part of their own unique exhibits.

McManus said that while the museum is eager to expand, she hopes that it doesn’t become too large.

“I hope more people can come out and look at it,” McManus said. “Learn about the local history, where we are now and where we’re going. I hope it grows, not necessarily in size, but in people.”

The collection to the museum grows every day and the work to catalog and preserve it all may seem daunting, but as long as Buxton, Hardin and a few dedicated students continue to be passionate about preserving the history of East Alabama, visitors from around the world will continue to be able to enjoy their unique insight into the cultural tapestry of the area for years to come.

A slideshow presentation is available here.

To view the accompanying multimedia presentation, click here.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.