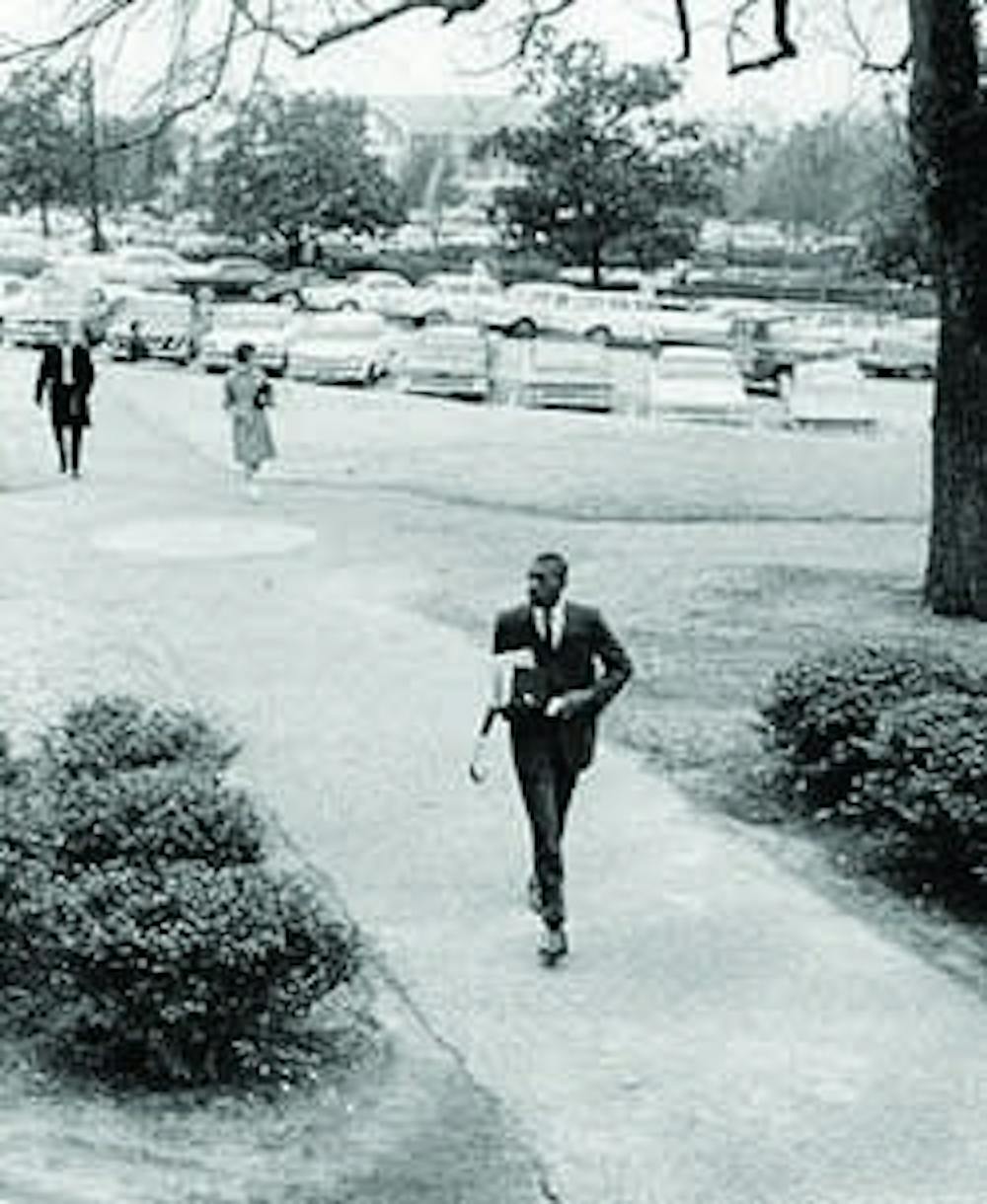

If one were to dig up an issue of The Plainsman from early 1964, one would find a story describing Jan. 4 as being "just another day on The Plains." This was the day Harold A. Franklin arrived in Auburn, soon to be the first black student at Auburn University.

Franklin had just graduated from Alabama State University and was living in Montgomery, seeking an institution where he could do graduate work.

"We got to the point where Hood and Malone had desegregated Alabama and we needed someone to desegregate Auburn." Franklin said. "Since I lived in Montgomery and I filled all the requirements."

Compared to the turmoil associated with integrating other southern colleges, particularly the University of Alabama and the University of Mississippi, Jan. 4 was just another day.

Franklin's arrival came seven months after Gov. George Wallace, who, in his inaugural speech, proclaimed "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever," stood in the schoolhouse door in Tuscaloosa to prevent black students from enrolling.

Franklin's first two applications were rejected.

"When Auburn turned me down it wasn't because I was black, at least that's what they told me" Franklin said. "They turned me down because Alabama State wasn't accredited."

Members of the Auburn Board of Trustees wished to avoid the same scenes that had taken place at Alabama and modeled their approach on Clemson University's uneventful admission of it's first black student, Harvey Gantt.

Dean Ralph Draughon said his goal was to "prevent the focusing of public opinion upon Auburn University," and "to present no target, or, as small a target as possible, to the advocates of integration."

Registration day was to be before the other students returned. The campus was sealed to all but authorized faculty, staff and security, and designated secure routes to Franklin's classes were organized.

Before Christmas break, Draughon had established a series of special rules to be applied upon the student body's return.

These called for students to take firearms home during the break and deposit them at the ROTC building if they had to bring them back.

They also forbade the congregation of large groups during registration and only allowed for the distribution of university-approved pamphlets or newspapers.

Aside from isolation in on-campus housing and social situations, Franklin's stay was uneventful.

"I've been to Auburn any number of times and I don't mind coming to Auburn," Franklin said. "I'm not the kind of person to carry a grudge. Nobody struck me physically, but had they struck me physically there would have been a grudge for the rest of my natural life. I would have struck back."

Franklin went on to complete his master's degree in history at the University of Denver and taught at Alabama State, North Carolina A&T University, the Tuskegee Institute and Talladega College.

Auburn awarded Franklin an honorary doctorate of arts in 2001.

"We're going to keep on struggling," Franklin said. "We're going to do what we know to be right, and then go on to make men and women out of ourselves; to make a positive contribution to society."

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.