The pioneering faces of computer science are men.

Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg and other male figures are often looked to as the creative minds behind the screens.

Raylyn Paschen, sophomore in software engineering, said many people see this and form a certain preconception: “Oh, coding is a guy thing.”

The lack of women in computer science has prompted discussions across the nation.

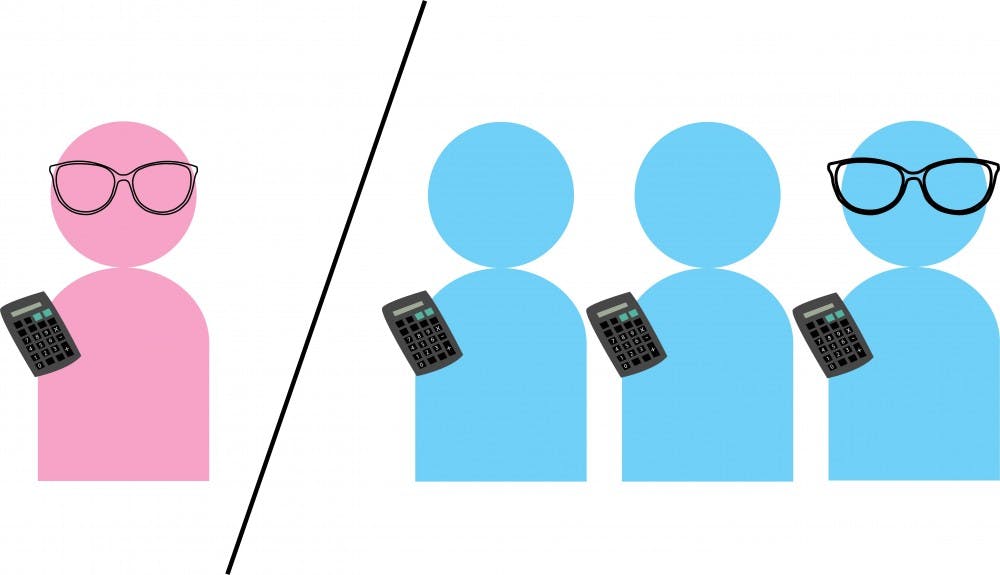

Seventy-nine percent of degrees awarded in computer science in 2016 were earned by men, according to Data USA, a platform for public U.S. government data.

Using data gathered from the Auburn University Office of Institutional Research, women earned only about 15 percent of degrees in computer science, software engineering and wireless software engineering during the 2017–2018 academic year.

Last March, Reshma Saujani, founder of the nonprofit organization Girls Who Code, spoke at Auburn on International Women’s Day about the gender gap in coding.

During her presentation, Saujani presented the idea that girls often are afraid to code because they are afraid to fail. She argued that young women are taught perfection rather than bravery as opposed to young men, who are taught that it is acceptable to be a risk-taker.

“We [women] are taught to smile pretty, play it safe,” Saujani said in March. “Get all A’s. Don’t get your dress too dirty. And our boys are taught to crawl to the top of the monkey bars and jump off.”

Annette Kluck, assistant provost for women’s initiatives, said the pressure of needing to be perfect can lend itself to creating a difficult environment in an area that primarily works through trial and error.

“In that field [computer science], it becomes part of how to be successful,” Kluck said. “It’s being able to try something, fail and tweak it until it succeeds.”

Jacqueline Hundley, senior lecturer in computer science and software engineering, said many female students are harder on themselves than their male peers.

“Girls tend to drop earlier than boys because they start doubting themselves earlier,” Hundley said. “They don’t always get that you can still graduate and be successful without a 4.0.”

Hundley, an Auburn alumna, had only one woman professor in her six years of Auburn math and engineering classes.

Hundley is a member of 100 Women Strong, a group organized through the College of Engineering and comprised of 167 female Auburn engineering graduates. The group’s members focus on retaining, rewarding and mentoring current Auburn female engineering students.

“We’ve all been there as the only girl in the class,” Hundley said.

Hundley said being one of few is always intimidating, but the young woman’s ability to handle it is what determines her success. In her experience, being the only girl in a class challenged her to work even harder.

“That’s just the way it was,” Hundley said. “It was, ‘I’m going to do this.’”

100 Women Strong and other on-campus organizations and initiatives are in place to make it easier to do that.

In research she conducted roughly a decade ago, Hundley found that female students generally prefer solving problems with solutions that are more helpful and beneficial to society.

“Girls are usually interested in doing things that make a difference in society,” Hundley said. “Whether you’re writing code or building something, we tend to think about what our contribution is going to be.”

According to a study conducted by Microsoft, 72 percent of women surveyed in grades five through 12, and 66 percent of women surveyed between the ages of 18 and 30 would describe themselves with the statement, “Having a job that helps the world is important to me.”

Kluck said when girls are raised with messages that they are expected to help other people and these values are internalized, it is important to consider how careers enable them to achieve high-reaching goals.

“We have to talk about the work in a way that helps girls realize they’re making people’s lives better,” Kluck said. “If we have biases about what women do, we’ll rule out careers that we don’t think are for women.”

Kluck also thinks it’s important to consider what children see from young ages and how it translates into what they view as possible or appropriate. She cited “Big Bang Theory” as an example.

“It’s a funny show,” Kluck said. “It does have some women scientists in it, but the ones who are in physics are all men.”

Saujani spoke to this, too, in her presentation.

“We have a Barbie doll who says, ‘I hate math, let’s go shopping instead,’” Saujani said. “I can walk into a Forever 21 and buy a T-shirt that says I’m allergic to algebra. All of you have watched Mean Girls, which I’ve watched on repeat, and you know the scene where she gets an A on a math test, and she crosses it out to a D, just to get the affection of a boy.”

Alexicia Richardson, a graduate assistant in computer science and software engineering, believes involving more young women in computer science fields begins with exposing them to coding in elementary, middle and high school.

“Obviously, the stereotype is that there are more men in engineering,” Richardson said. “I feel introducing coding to girls early would definitely increase the amount of females in the major.”

Dana Davis, freshman in computer science, said though it can be intimidating, her high school STEM experiences prepared her for life in the minority.

“My high school robotics class, junior year – I was the only girl,” Davis said. “I know what it’s like.”

Davis began coding her senior year of high school in an AP computer science class.

“In that class, I just kind of accepted that this is going to be a very male-heavy major,” Davis said.

Data published by the National Center for Education Statistics indicates that in 2015, only 22 percent of the approximately 55,000 students who took the AP computer science exam were female.

In the same year, there were three states in which no girl took the exam.

Paschen, too, began her coding career with a class in high school.

“If I hadn’t taken that class and had walked in [college] the first day to see I was the only girl, I think I would have walked back out the door,” Paschen said.

Paschen said she’s noted the lack of female classmates since her first coding class at Auburn. She said the overwhelming male majority can leave her with a subconscious feeling that she knows less than those surrounding her.

“When I get stuck, I’ll feel like I’m the only one hung up,” Paschen said. “I know logically there’s probably a lot of other people struggling with it too, but there’s this irrational fear I’m the only one who can’t figure it out.”

Paschen finds herself hesitant to actively participate in class-group chats dominated by young men or ask questions in class at risk of being seen as “the dumb girl.”

She doesn’t feel treatment in her classes has been or is different for men and women. Her fears are generally not caused by external aggressors so much as internal questions, Paschen said.

“You see you’re one of the only girls and you think, ‘Did I not get the memo?’” Paschen said.

Paschen said she does not have any female friends in her area of study with whom she can discuss these thoughts. She thinks in time, though, girls in coding will become less out of the ordinary.

“Once more girls get into it,” Paschen said, “girls won’t be doubted.”

Richardson said that since she first arrived as a wireless software undergraduate student in 2013, she’s begun to see an increasing number of young women entering the majors.

“I’m a TA now, and I can see the margin slowly decreasing,” Richardson said.

Richardson said many men in the program are inclusive, and classwork is the same regardless of gender. She didn’t truly notice the impact the gap could have on students until she began working in group projects — groups where she was the only girl.

“Every now and then, my voice wouldn’t be heard,” Richardson said.

Richardson said when she is in a group full of boys and they don’t listen to her input, the automatic first assumption is it’s because she’s a girl.

Richardson said not all men ignore her feedback, but the ones who do need to realize she is equally as capable as them.

“The fact that you’re a guy, and I’m a girl, doesn’t make me any less of a programmer than you,” Richardson said.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.