Fifty-seven years have passed since Harold Franklin walked across Auburn’s campus as its first Black student.

On that day, surrounded by a personal detail of federal and University guards, Franklin was escorted to Magnolia Hall, where an entire wing had been emptied out for him to live in. He then made his way to the library, where he registered as an Auburn student and received his books.

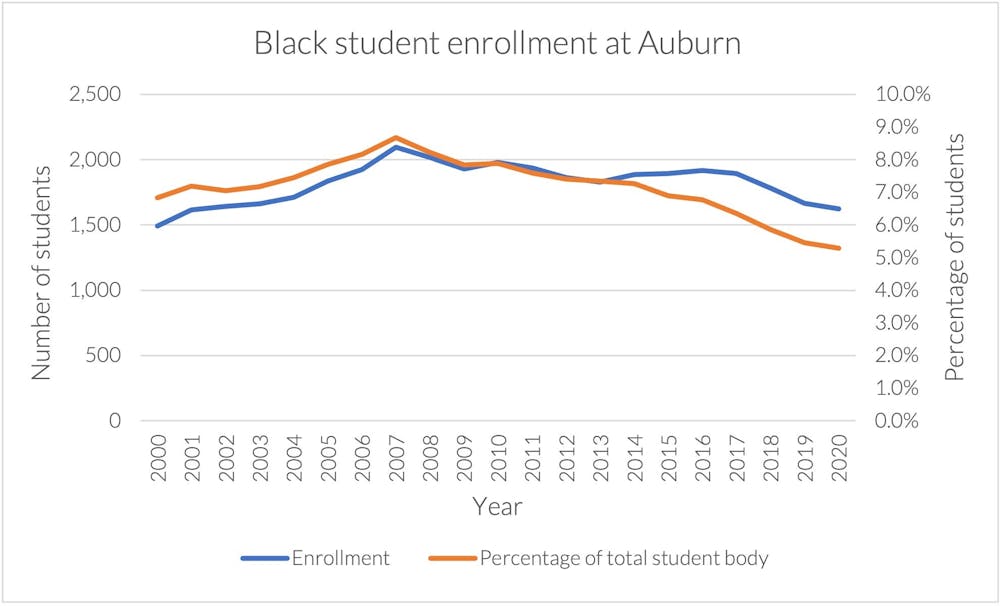

Over the subsequent years, Auburn began to admit an increasing number of students of color, aiming to make the changes necessary to desegregate not only in definition but in culture. 2007 marked the year with the highest percentage of Black students at Auburn since 2000, with 2,096 students making up 8.7% of the student population, according to the Office of Institutional Research.

Since 2009, Black students have made up less than 8% of the student population at Auburn.

Since 2007, the number of Black students and the percentage of the population that they make up has steadily fallen. In 2020, the most recent data on record, 1,624 Black students made up 5.28% of the student population. For comparison, in 2020, there were 4,145 Black students currently enrolled at the University of Alabama, making up 10.95% of its student population. In the same year, there were 3,321 Black students currently enrolled at The University of Alabama at Birmingham, making up 23.9% of its undergraduate population.

In 2018, the Race and Equity Center at the University of Southern California published a report ranking Auburn University in the bottom 20 percent of colleges for racial equity.

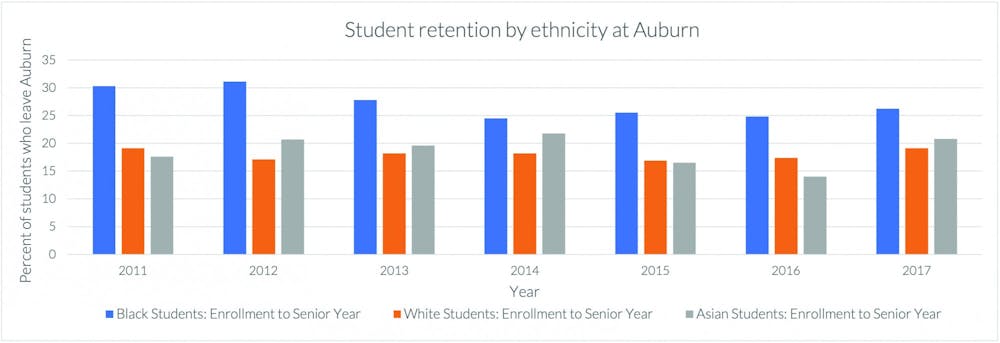

Retention rates for Black students at Auburn also differ significantly from their white and Asian counterparts. The average change in the percentage of enrollment from second semester of freshman year to first semester of junior year for Black students from 2010-2018 was 18.10%. Essentially, this number represents the percentage of Black students who left Auburn’s campus in that time period. This number was 11.42% and 12.31% for white and Asian students, respectively.

While the numbers can be confusing, the fact remains that Black students are not only admitted at an increasingly lower rate than other ethnicities, but Auburn also retains them at a much lower rate.

“Numbers don’t really lie,” said Tyler Ward, junior in political science. “I think that it is very ignorant to think that everyone has the same opportunity, [to think] that even if you give everyone the same opportunities, they will be able to do the same things.”

Of the three largest racial demographics at Auburn, Black students consistently have the lowest retention rate for any given time period. The year listed represents the year each class enrolled at Auburn.

At Auburn, these numbers can be looked at to quantify just how diverse and inclusive the campus is, but by definition, the metrics one uses span far past numbers, according to Taffye Clayton, associate provost and vice president of Auburn’s Office of Inclusion and Diversity.

“Diversity, simply put, is all the ways human beings are different,” Clayton said. “By nature, its definition is very broad and encompassing. Inclusion is involvement and empowerment that recognizes the inherent worth and dignity of all people. An inclusive university promotes and sustains a sense of belonging and values and respects the identities, talents, beliefs, backgrounds and ways of living of organization members.”

Clayton and her team at the OID aim to enrich the experiences of all members of Auburn’s campus through the lens of diversity, equity and inclusion. While the specific title is one that she has taken at Auburn in recent years, Clayton credits her experiences as a young child in Fayetteville, North Carolina, for fundamentally shaping the way that she works. She said this prepared her for the issues she now faces at Auburn on a daily basis.

“I was very active in theater as a young child,” Clayton said. “Ultimately, this put me in contexts that were very diverse and heterogeneous. I was also a military kid. While we worshipped at a church that was predominantly Black in our neighborhood, we would also make visits to the main post chapel that was very international and diverse in its nature.”

Before coming to Auburn, Clayton served at East Carolina University as associate provost and chief diversity officer. After that, she took on the position of associate vice chancellor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, her alma mater, where Clayton’s role mirrored her experiences there as an undergrad.

“In college — at UNC — I was a resident advisor,” Clayton said. “I had an opportunity to have responsibility for students, and at a predominantly white institution, that meant a lot of diversity around me. All told, my life has been enriched by these [diverse] experiences.”

OID’s role is to inform the strategies that lead to improvements in diversity, equity and inclusion performance and progress indicators, Clayton said. These goals are not just for her office, but for the University in its entirety. Being a data-driven unit, her team uses different metrics and multiple assessment modalities to provide evidence and support for their work.

The work Clayton’s team does shows up in many different ways across Auburn’s campus, she said. Her education team hosts training sessions on microaggressions, implicit bias and psychological safety for staff and departments on campus and leads efforts to examine the experiences of historically underrepresented and marginalized communities.

“We have a goal of launching a University-wide diversity statement that can be used across colleges, schools and academic units,” Clayton said. “This semester, following faculty recruitment and retention recommendations from the Presidential Task Force for Opportunity and Equity, we are launching an Auburn Faculty Initiative designed to strengthen the recruitment and retention of historically underrepresented faculty at our institution.”

In order to integrate these policies into the Auburn community, OID relies on its student ambassadors to inform underrepresented students about resources to help them succeed and excel, as well as to implement the best practices for recruiting and retaining students from diverse backgrounds. Ward, from Demopolis, Alabama, spoke about his experiences as a high school student regarding these topics.

“I think that a lot of the time, the root of these issues [does] go back to high schools,” Ward said. “'Cause I’m from Demopolis, which is the same kind of area as Greensboro, and I didn’t even realize how bad those school systems were until I got to Auburn. I thought that everyone only took the ACT once, that everyone only [took] [Advanced Placement] classes but never really passed them, that everyone really came from that background. Then I got here, and I realized that that wasn’t the case.”

For Ward, a tangible example that highlights this discrepancy in education and equitability is the number of students who attend the University from both Auburn and Opelika’s high schools. In 2019, 192 students from Auburn High enrolled in Auburn, while only 18 students from Opelika High enrolled in Auburn. Auburn High’s total student population for 2019 was 1,843 with Black students making up 21.43% of the population and Opelika High’s was 1,201 and 57.62% respectively.

“Just letting higher government officials and those who are chosen to represent us … know that high school education [does] have to be more fair,” Ward said. “Whether that’s us going to those high schools to see what they need, maybe that’s us providing that ACT prep or tutoring; seeing how we can get those students here. I think that also falls on Auburn administrators to advocate on our behalf and the high school student’s behalf.”

Each of these individual pieces falls together to make up the environment and climate of Auburn’s campus. According to Clayton, understanding how Auburn’s students, faculty and employees are experiencing the environment is critical to effectively advancing diversity, equity and inclusion work.

“The puzzle pieces are coming together,” Clayton said. “[This] work does not take flight without collaboration. It takes commitment, institutional will, strategy, resources and action to advance diversity, equity and inclusion to become among the leading universities in this area.”

The collaboration from students must come from a place of humility and grace, Ward said. When talking with someone who does not share the same beliefs, for Ward, meeting them halfway is the best thing that one could do.

“My job, and the job of OID and the job of Black students is never to convince people that systemic racism is real — it’s only to give them the information and to let them decide for themselves,” Ward said. “I think the more that we try to tailor our message to people who have decided to oppose what the facts are, the more we are doing a disservice to ourselves and just wasting our time … trying to educate the people who refuse to be educated.”

Clayton’s office seeks continuous improvement. Each year, she said, her institution should expect and deliver increased progress on diversity, equity and inclusion indicators.

“It will not always be easy, but taking the time to learn, grow and act together as a community is the best way forward,” Clayton said. “There’s clearly more work to be done, and we intend to put in the work that’s necessary to make progress.”

Having honest conversations is something that Ward believes in strongly.

“I think that comes from humility and grace, and just really understanding that a lot of people are ignorant and they come from situations where they haven’t been exposed to those different kinds of things,” Ward said. “Honesty and truthfulness are embedded into the [Auburn] Creed for a reason — I think that if we only choose to ignore that when it becomes uncomfortable, then it becomes unnecessary, wrong and isn’t really who Auburn is, what we do, or who we are.”

This is the first in a series of stories exploring issues of racial equity and diversity on Auburn’s campus. This article provides a background on these issues as well as the role of OID. Data for infographics in this story were sourced from the Auburn University Office of Institutional Research.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.