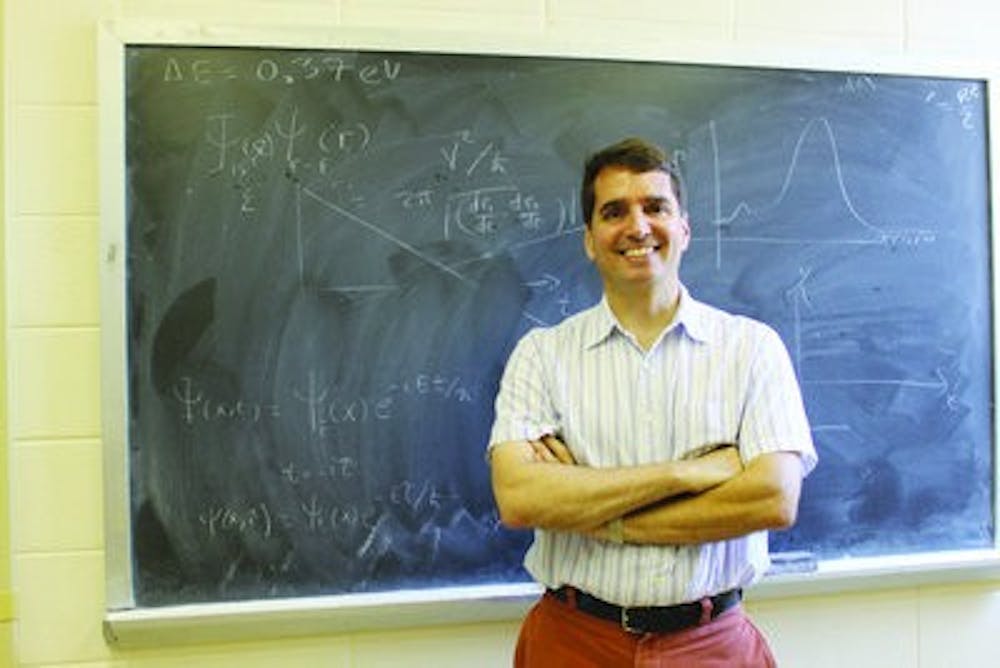

Auburn University physics professor Francis Robicheaux was recently mentioned in the "Nature Physics" journal June issue for his role in the Anti-Hydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus (ALPHA).

Robicheaux, along with a group of international scientists, has been able to trap and hold the antimatter version of the hydrogen atom, which is a significant breakthrough in science. Robicheaux serves as a theorist to the team, providing computer simulations when needed.

The research collaboration's headquarters are at CERN, which is Europe's particle-physics lab, located in Switzerland. ALPHA includes scientists from North America, Europe, Brazil, Japan and Israel.

Robicheaux said the most recent paper published in "Nature Physics" is a great step forward in the team's research.

They can now hold the atoms for up to 15 minutes where, at the beginning, they were only able to hold them for a little under one second. According to Robicheaux, the added length of trapping the atoms will also lead to a better study in their dynamics.

"It's very difficult to trap anti-hydrogen," Robicheaux said. "We have made significant process in lengthening the time that we are able to hold the anti-hydrogen atoms, which will allow us to experiment longer and measure the properties of the anti-hydrogen."

Donnan also said that this research is important in a sense that it has the potential for grand discoveries.

"I think it's important because it can test the fundamental assumptions of how our universe was created," Donnan said. "Hopefully, our research and experiments can shed some light on why our universe is made of matter and not anti-matter."

Patrick Donnan, sophomore in physics and music performance, has worked with Robicheaux in his research and said he understands the importance of this breakthrough and what it means to Robicheaux.

"Dr. Robicheaux is more enthusiastic about physics than anyone I know," Donnan said. "He is incredibly active in atomic, molecular and optical (AMO) physics and most of the work I have done for him is for the ALPHA collaboration."

Donnan also said while the research is important, being a student of science is what makes it interesting to him.

"To me, it's really cool, especially for science students who keep up with current events," Donnan said.

Kelsie Niffenegger, senior in physics, has also helped Robicheaux with his research.

"I think it's just really cool to kind of be a part of the first group to make these discoveries is cool. I can't wait to see the future applications of this research," Niffenegger said.

Despite the success of the research, it has not come without its problems. According to Robicheaux, the biggest problem that the team has is making the anti-hydrogen cold enough to grab.

"Anti-matter protons and electrons are quite hot," Robicheaux said. "And we have to hold it with either an electric field, which is neutral, or a magnetic field, which doesn't give us enough force. So we really have to make them colder in order to experiment like we want to, in terms of length and the types of experiments we can do."

Though great strides have been made with anti-matter research, there is still limitless potential to learn more about its properties.

"This paper that just came out is sort of the next stepping stone in the path of doing the actual measurements of the properties of the anti-hydrogen," Robicheaux said. "That is really our main and long term goal."

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.