On Sept. 11, 2019, the sky over Auburn got a little darker.

One of our stars, Anne Rivers Siddons, a bestselling author and Auburn alumna whose work is an outstanding example of the power held in bitingly candid writing, passed away that day.

Siddons wrote columns and editorials for The Plainsman before graduating from Auburn in 1958, and her dismissal from The Plainsman’s staff during the height of segregation should serve as a lesson for the intentions, importance and consequences — good and bad — of journalistic opinion writing.

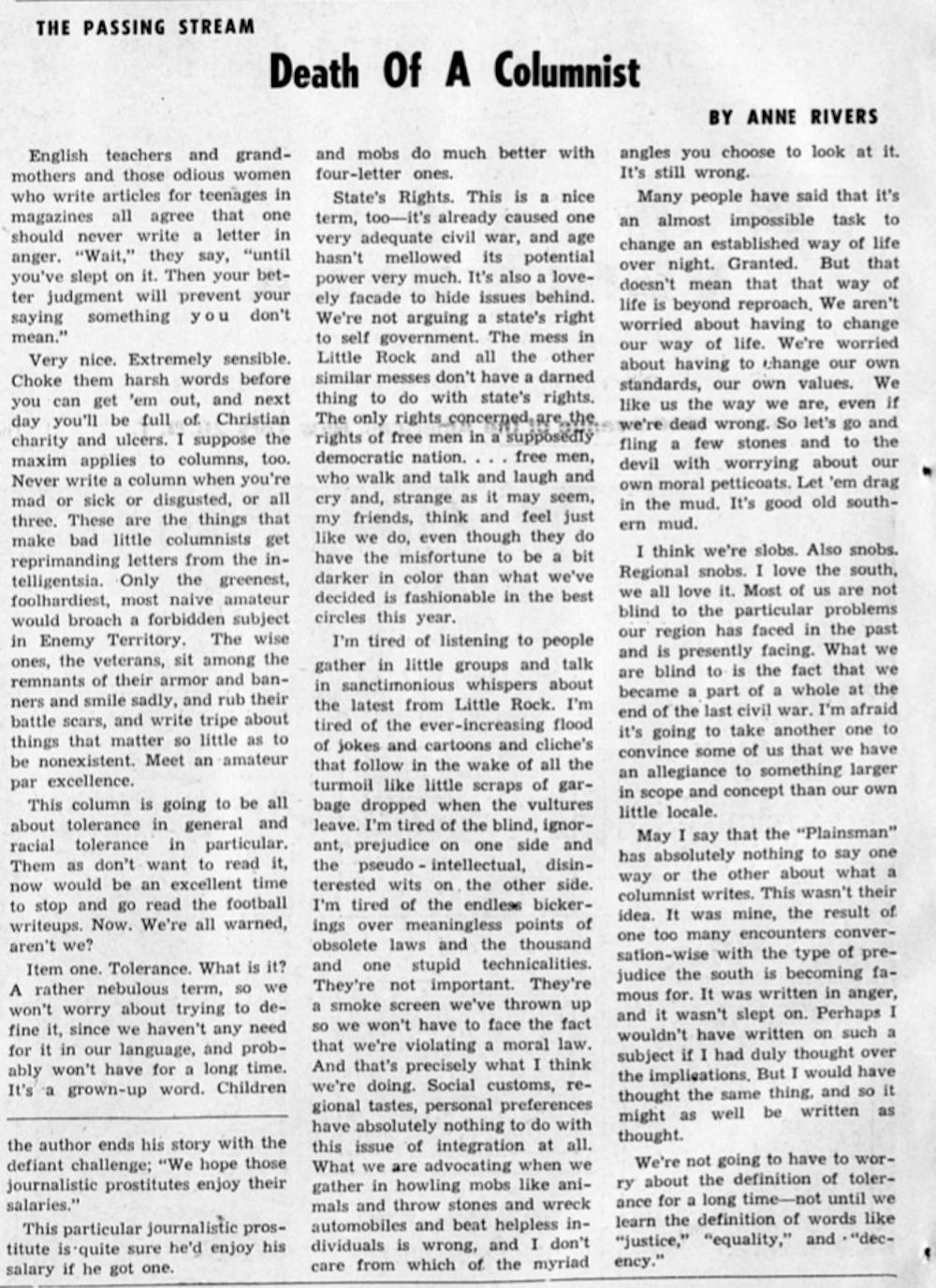

The column that Siddons got the most backlash for was published in October 1957, seven years before a student of color would enroll at Auburn, and was titled, “Death Of A Columnist.”

Siddons described the piece as being about “tolerance in general and racial tolerance in particular.” Knowing her audience, she then invited people who didn’t want to read her article to “go read the football writeups.”

Siddons derided the people opposing integration by saying they gather “in howling mobs like animals and throw stones and wreck automobiles and beat helpless individuals.”

She called on the “regional snobs,” who insisted on maintaining the South’s traditions of injustice and segregation to quit “worrying about our own moral petticoats. Let ‘em drag in the mud. It’s good old Southern mud.”

Her words were brutal, they were honest and they were controversial.

At a time when inclusion and equality were deemed radical in the South, Siddons wrote columns proudly supporting racial tolerance and criticized the racist mobs fighting integration.

And it cost her.

Initially, an administrator from the University attempted to suppress the columns, but when that proved futile, Siddons was fired from the newspaper’s staff.

Despite — or perhaps because of — this attempted silencing, Siddons’ column garnered national attention.

Her call for justice and explanation of tolerance resonated with readers across the country and started a conversation on campus.

The next three issues of The Plainsman had either letters to the editor or columns debating Siddons’ piece and the larger topic of integration in the South.

Many of the responses published during that time were staunch refusals of Siddons’ call for integration — one called her a frustrated old maid — but a select few supported her.

“Many of us agree with Miss Rivers and hope that her thinking has had some effect on students at Auburn,” a student wrote anonymously.

Some writers, like Frederick B. Benson, disagreed with Siddons but still supported her right to write her opinions and publish them.

Benson said her column was “thought provoking, and whether you agree or not with their views makes no difference. You are at least stimulated which is much better than being subjected to the inane trivia which usually appears in print.”

Siddons knew her opinions would be controversial, but she wrote in a way that made them conversational.

Now, 62 years after “Death of A Columnist” was published, the legacy of the conversation Siddons started should be a reminder of why independent and open-minded opinion pages are vital.

The goal of journalism is to uncover interesting, pertinent or critical information and then present it in a way that is understandable and impactful.

It’s about honesty, clarity, accuracy and relevancy.

We report the facts and tell the stories that we think our readers need or want to know.

That hasn’t always been the goal of journalists — many of the earliest newspapers were organized and run directly by political parties — but the formalization of journalistic standards at the start of the 20th century saw newspapers pride themselves on being independent and unbiased.

At that time, opinion pieces and letters to the editor were relegated to their own pages.

For the next 100 years, even as new media were created, existing media were altered and outdated media were abandoned, most of the major American news outlets kept a boundary line between reporting and editorializing.

But some of that has begun to change.

The development of 24-hour news channels, online publishing and social media has eroded much of that boundary line.

Pundits now dominate the airwaves and the host of the most watched show on the most watched news channel has openly campaigned for a political figure who calls the media “the enemy of the people.”

The news will always be inherently political, but we are in a situation where some of the most prominent journalists in the country are acting politically.

This degradation has created mistrust and given voters an excuse to defame journalistic bastions for publishing an article that is critical of their favorite candidate.

By keeping reporting and editorializing wholly separate from each other, news outlets can start to rebuild trust among the large swaths of the public where they have lost it.

Clear distinctions between reporting and opinion give legitimacy to organizations and allow for the public, en masse, to at least agree on a set of facts.

Then, with agreed upon facts as a basis, columnists and contributing writers can make arguments for the societal, moral and political implications of a situation — they can start a conversation.

They can ask questions about why something happened, rather than if it happened at all.

Independent and clearly defined opinions sections produce and thrive off of controversial writing.

In turn, well-written editorials and columns invite readers to respond with letters to the editor.

It becomes a feedback loop where we all can debate moral and political issues without hurling phrases like “fake news,” around.

Looking back to 1957, plenty of readers disagreed with Siddons, but none of them accused her of lying.

They thought she was wrong, but they supported her right to speak and believed her opinions to be honestly held.

Conversations like the one started by “Death of A Columnist” are vital to our democratic and journalistic process, and it shouldn’t take the actual death of the columnist to remind us that.

This editorial is the majority opinion of the Editorial Board and is the official opinion of the newspaper.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.