About the series

The "Auburn voices from the pandemic" series is an oral history from The Plainsman of COVID-19 and how people are being affected by the disease.

As told to Eduardo Medina

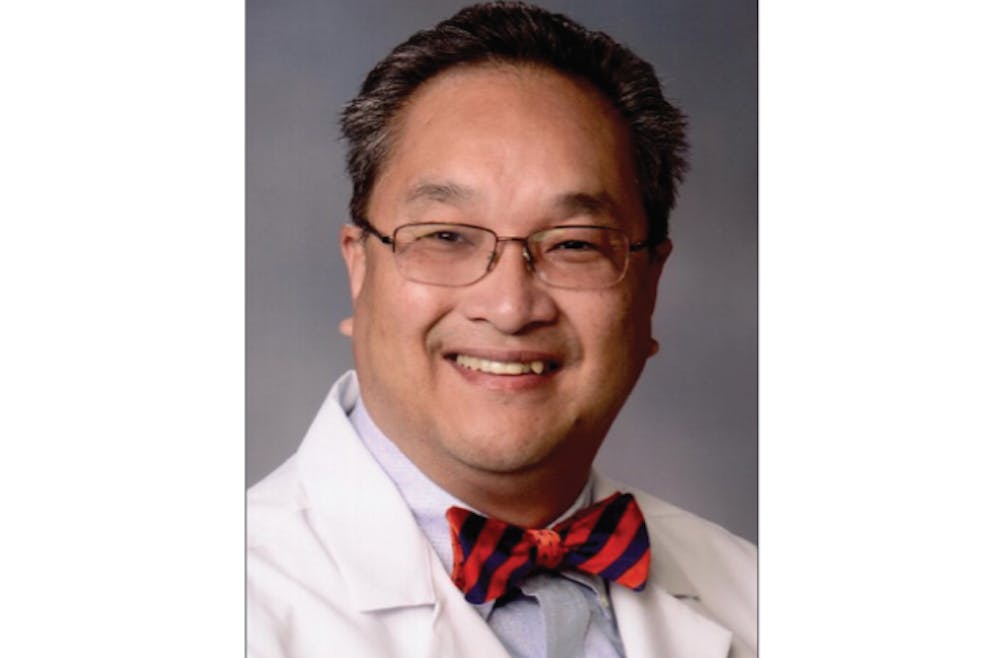

Dr. Fred Kam, medical director at the Auburn University Medical Clinic, discusses how COVID-19 is taking a toll on healthcare providers in Auburn. His oral history was made possible through an interview he granted The Plainsman on Wednesday, April 8, 2020. The transcript from that interview has been slightly edited for clarity and rearranged for structure to produce the following piece.

The Auburn University Medical Clinic on Saturday, Dec 10, 2017.

"The real toughest day was when the first case was identified."

You know, the real toughest day was when the first case was identified. That confirmed to us that it was finally here. It was no longer, “When will it be?” When was now. We expected it, but like anything else, when you have to deal with it, it becomes real.

Since then, there’s been a lot of rumors. Everyday, a new rumor that you gotta chase down. You gotta make sure it’s either valid or invalid. Unfortunately, most of them have not been valid. People will say, “I hear there’s an outbreak at this apartment complex.” So we’ll say, “Can you give us the names of individuals that you hear have COVID-19 there?” Right after spring break, there was a rumor that students in campus housing were diagnosed with COVID-19. All of those rumors turned out to be false.

I’ve stopped seeing patients directly because of the coronavirus. About one-third of my team, on any given day, has been deployed to EAMC to help. Another part of our team is at the testing center. The rest are answering phone calls, messages. My team and I decided I’d be the individual to lead the process of communication. So I wake up at 5:45 a.m. and read the data that came out overnight. At 7:30 a.m. I'm in my office at the clinic, and I look at data again. Then I proceed to get on Zoom meetings with university leadership at 8 a.m then again at 9 a.m. The president, the provost, representatives from the faculty and staff, the SGA president, the athletic director, they’re all in these meetings. I try to predict to them what I believe is coming. Online classes for the rest of the semester, postponing graduation — I’m trying to predict when we will be in the outbreak process and when we might have to take certain actions.

“When is this going to end?”

People ask, “When is this going to end?” It depends on what you mean by end. End in that the virus has gone away, there’s no more infection? No. I’m not optimistic about that at all. I think we’re going to be dealing with this for the next year or couple of years.

I meet with my team at 11:45 a.m. This is such a fast-moving process, we meet three times a day. We probably spend more time with each other than we do with our families. Knowing that at any given time, we can have people who are asymptomatically carrying around this virus and that, at any given time, some of my staff can be unknowingly exposed — it weighs on me.

We had four people in the clinic that came down positive with COVID-19. The origin wasn’t with a patient. It actually started with one of the employees who got it from a family member at home. The minute the employee started getting symptomatic, they were out. We told the employees who were around that person to stay home, too. Luckily, we didn’t have an outbreak. That happened a couple of weeks ago. Some of those employees who tested positive are already back to work. An outbreak like that can happen at any given time, and those things weigh on you. I mean, the United States was once one plane passenger away from having an outbreak. Back in January, we were focused on one country: China. Here we are in April, and it’s in over 180 countries across the world. That’s how quickly it happened. I think about how China locked down Wuhan, and I think about trying to lock down Auburn, Alabama, where we only have 50,000-60,000 people. I can’t even fathom trying to do that here.

Dr. Fred Kam, Dr. Ricardo Maldonado and Brooke Bailey hold a press conference to address the threat of coronavirus on March 5, 2020.

"Just because COVID-19 came into being doesn’t mean everything else stopped."

We’re very concerned about the outbreak in Lee County. If people don’t do what they’ve been asked to do, we could get overwhelmed. Both at the clinic and at EAMC. Just because COVID-19 came into being doesn’t mean everything else stopped. We’ve still got students who have mental health issues, and a lot of them have exacerbations right now. We’ve got them on medication. We’ve got students with diabetes and asthma, students with GI symptoms and diseases. All of those still exist. A lot of students aren’t in town right now but, to our credit, we have students who will call us from Indiana and say “I’m sick.” And they expect us to take care of them. But as more and more people come down with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, we have to be very rapidly responsive to those people. Getting overwhelmed would really hurt us and our patients. Yesterday, one of our doctors played guitar and tried to uplift everyone at the clinic.

When we get comments or pictures from people, saying “Look at all of these people sitting around the pool,” when we get stuff like that, you know, it’s frustrating. How long can we say it? The only weapon we have against this outbreak is physical and social distancing. It’s what we’ve been preaching for weeks. Where else can we say it? When else can we say it? Hearing stuff like that from people, it’s just going to have a real impact on the trajectory of this outbreak.

I always finish the evening in my office until right around 7 p.m. I have a whole process for when I get home so I don’t expose anyone in my household. I change out of all my clothes, and I clean everything. My mother-in-law lives with us. She’s over 80 years old. We’re doing everything we can to make sure she’s protected.

We all have dinner as a family. Last Friday, I cooked salmon for them. And I told my kids that they’re responsible for a meal every weekend. It works out really, really well for me and my wife. We have fun doing that.

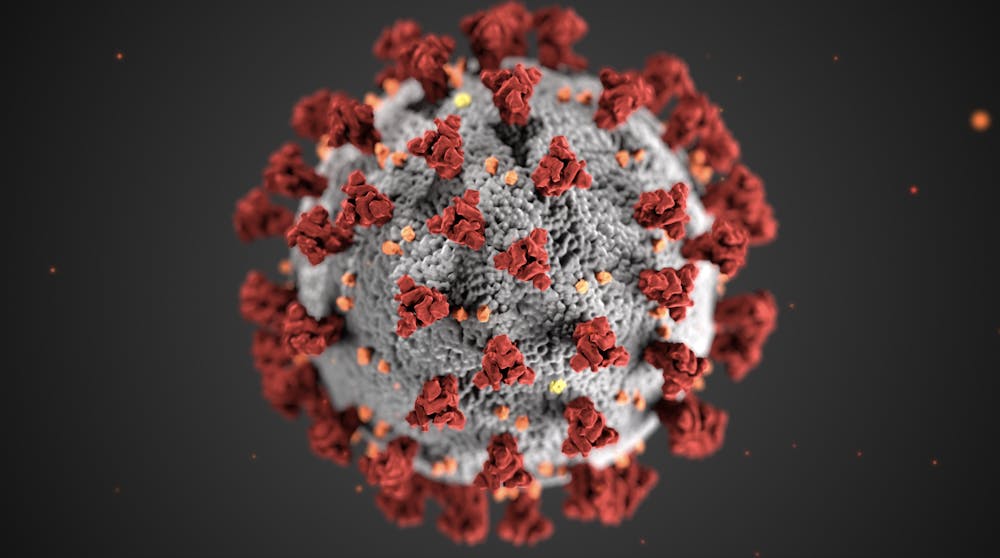

This illustration, created by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronaviruses. The illness caused by this virus has been named coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19.

"They’re silently very concerned."

I think they’re silently very concerned, my family. You know, they’re concerned for my health when I’m here. They see how serious I take the process. I don’t mean this arrogantly, but they know what my passion is. My wife, who I met when I was a lot younger, she knows my commitment. She’s seen me work hundred-hour work weeks before. I was a young doctor when AIDS started breaking out in the states. So this isn’t new for her. But she reminds me that I’m not as young as I used to be. She says, “You can’t drive yourself as hard as you did back then.” I said, “No, I’m a lot wiser. I’m taking care of myself.” But yes, I see their concerns.

I knew I wanted to be a doctor when I was seven years old. When I was growing up in Trinidad and Tobago, we had a polio outbreak. I was a really altruistic child and teenager, so I wanted to be a doctor and cure the polio and cure diseases and save the world. I’d hear about diseases in other countries, and I wanted to learn how to fix them. That was always my calling, you know? I got into medicine, and that’s what I trained to do.

All of this has been challenging. It’s hard because there are a lot of questions we don’t have answers to. Can I get it again? We don’t know. How long will these symptoms last? Well, we can’t exactly tell you how long it’ll last for you. Is there something I should be doing or eating or drinking to get better? We don’t know. There are a lot of unknowns. That makes this incredibly hard. Here’s someone who has a disease and is asking questions, and you’re telling them, “We don’t know.” As a professional, you’re not giving them a great level of comfort. So then that makes you uncomfortable. You don’t like to deal with unknowns in medicine. You like to heal. And we’re not doing that right now.

I spend another two or three hours at night researching COVID-19. I normally go to bed around 11 p.m. or midnight. There’s so much data going around my head, it’s hard to stop thinking about it. It’s hard to shut off and go to sleep sometimes. Once Sunday hits, I get ready for the rest of the week. Then I’m up at 6 a.m., reading data again.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Eduardo Medina, senior in journalism, is the editor-in-chief of The Auburn Plainsman.