Aniah Blanchard’s murder and kidnapping have prompted her family and friends to look to make changes. That includes promoting Aniah’s Law, which would restrict pretrial release on bail for an extended number of violent offenses, and starting the nonprofit organization Aniah’s Heart.

“I’m going to make sure that her life meant something and that we’re together going to save lives because of what happened to her,” said Angela Harris, Aniah’s mother. “And so that’s really what’s keeping me going. I just — I can’t give up on Aniah.”

I. Seeking Change

Following Aniah’s death, Harris looked for a way to make a positive change in the community.

“Her death is not going to be in vain,” Harris said. “She gave her life to stop that monster,” she continued, speaking of Ibraheem Yazeed, who is accused of Blanchard’s kidnapping and murder.

Harris has worked to channel her energy from Aniah’s passing into positive change with the nonprofit organization Aniah’s Heart. Through Aniah’s Heart, she hopes to educate people about how to stay safe in a public that she feels is becoming more unsafe.

She has led both public and private lessons on self defense and how to stay safe since founding Aniah’s Heart. She plans to lead charity events, fundraising events and go to schools and colleges as part of the organization, and hopes to make Auburn one of her first stops.

“We’re focusing on Auburn first because, you know, that’s where it happened,” Harris said. “That was where Aniah lived, and that’s where Elijah lives, and they loved Auburn.”

The nonprofit also serves as a resource for families who have gone through similar tragedies. Aniah’s Heart has helped two families in their search for a missing loved one, Harris said, and she hopes to continue doing so in the future.

“We’ll continue to do that, because people don’t know what to do,” Harris said. “We didn’t know what to do, and when you first learn your loved one’s missing, where do you go? What do you do? Because, you know, the police can only do so much.”

Aniah’s older brother Elijah, Auburn University senior in supply chain management, and her former roommate Sarah O’Brien have also been involved with Aniah’s Heart. Elijah has become passionate about self defense, something that he didn’t pay much attention to before Aniah’s death.

Elijah said he felt that people aren’t aware of their surroundings when they go out, which worries him. He used to do the same thing.

“I was one of those people,” Elijah said. “I didn’t pay attention to it because I thought it would never happen to me.”

He said he’s come to realize that horrible things — like what happened to Aniah — can happen to anyone. Now, he plans to turn this new passion for self defense into a business.

“It’s really just given me a goal bigger than just myself,” Elijah said. “It’s given me a mission, instead of just a way to make money.”

Aniah’s kidnapping and murder also led Hannah Crocker, one of Aniah’s long-time best friends, to change her career plans.

When Crocker went to college in 2018, she was planning to become a nurse. She enrolled at Shelton State Community College in Tuscaloosa, started working shifts at DCH Regional Medical Center and was enjoying it. But after Aniah’s death she decided to go into policing and has since enrolled in the police academy.

She described her experiences with police officers as “not fantastic” during the early days of the investigation into Aniah’s case, which she said was mostly outside their control. They just hadn’t been through anything like that before.

“The officers did everything that they could — they weren’t given much to go off of,” Crocker said. “But at the same time, I’m like, it might ... have been nice to talk to somebody that was like, ‘Oh hey, I completely understand.’”

Now that she has gone through that situation, she said she’s in a good position to empathize with the families and friends of people who suffer the loss of a loved one.

II. Aniah’s Law

Aniah’s Law is a bail reform bill currently being considered in the Alabama legislature that would allow defendants accused of certain violent felonies to be held without bail.

Alabama Rep. Chip Brown of Mobile wrote the bill and presented it to the state legislature.

“What [Aniah’s Law] does is it allows someone that’s charged with a violent, Class A felony, which would be rape, murder, violent domestic assault, kidnapping — those types of crimes that are violent crimes against an individual, against another person — if they’re charged with that, the prosecutor can ask the judge that the individual be held without bond,” Brown said.

Bail is the amount of money that an arrested individual may be required to pay to leave prison before their trial, which is returned to them if they show up for their court date. When individuals cannot post all of their bail, they may contact a bail bondsman to post their bail for them, in exchange for a bond payment, a fraction of bail. Often, these terms are used interchangeably.

Yazeed, accused of the kidnapping and murder of Aniah, was out on bond for another kidnapping charge at the time of her disappearance, among several other counts.

“In American jurisprudence, you’re innocent until you’re proven guilty,” Brown said. “[But] there are certain individuals that need to be held [without bond] because they are a threat, an imminent threat to society. That’s where Aniah Blanchard’s case comes into play, is that the individual that’s accused of her crime was out on bond for a robbery, kidnapping and attempted murder, and he shouldn’t have been out.”

If this legislation had been in effect before Yazeed was granted bond, Brown said, “[Aniah] would be alive today.”

Currently, bail can only be categorically denied for capital offenses.

Under Aniah's Law, once the prosecutor requests the denial of bail, Brown said, the court would hold an evidentiary hearing where the prosecutor must “present evidence that the individual is an imminent threat to society or a threat to themselves or is a flight risk.” After this hearing, the judge would decide whether or not to grant bond.

Passing the legislation would require an amendment to the Alabama Constitution that would need to be voted on in a public election, as it would amend the section on excessive bail.

Brown said that while he had been interested in writing bail reform legislation for some time, Aniah’s story, and others like it, really “brings it home.”

“Aniah’s mother, Angela Harris, had asked me if I would consider naming the bill in honor of Aniah, and I said certainly,” Brown said. “They were very involved, both sides of her family.”

Harris said she spoke to the legislature several times during the last legislative session in Montgomery. Harris said she sees the amendment as a way to start to fix a criminal justice that she said “needs a lot of work.”

“We have to do that,” Harris said. “Together, we’re going to have to demand that things change the law, like Aniah’s Law. So we can’t count on anybody else to keep us safe but us.”

The bill passed unanimously in the Alabama House of Representatives and the Senate Judiciary Committee. However, the process screeched to a halt when COVID-19 shut down the state legislature completely in March.

The very Thursday that the bill was set to be presented on the Senate floor, Brown said, the session was canceled and the legislature temporarily disbanded over coronavirus concerns.

Brown said that while the bill must start its approval process again from the beginning for the new 2021 session, he will prefile it so that it will be taken up quickly. He expects that both of Aniah’s parents will speak again at the 2021 legislative hearings.

“I think that it’s important that people understand the current law,” Brown said. “Because there is that thought out there that you can be held without bond, but that’s really not the case, unless you’re charged with capital murder. This is an effort to really save lives.”

Brown said Aniah’s family has been outspoken in their support of the bill, and he encouraged interested residents to speak to their House and Senate representatives to voice their own support.

“It’s got a lot of support,” Brown said. “It’ll be the same piece of legislation that passed the House last year. … I would expect to have that same level of support this year since it’s the same exact legislation.”

While the legislation was overwhelmingly popular when it was introduced in Montgomery, there are some legal scholars who are wary of the policy it promotes.

Jenny Carroll is the Wiggins, Childs, Quinn and Pantazis Professor of Law at the University of Alabama School of Law. Carroll, an expert in criminal defense and criminal procedure, said she thought the legislation could have detrimental effects on communities and create some pressing legal questions.

One important thing, she noted, is that individuals who are held pretrial have not been found guilty. However, they are held in the exact same place as convicted criminals, often in the same or even worse conditions, Carroll said. Yazeed is currently being held in Lee County Jail.

There are also questions of funding that need to be answered, Carroll said. More bodies in cells means more dollars to prisons, and it is currently unclear where such funding would come from, she said. The costs would mostly fall to county and local governments.

However, Brown said cost estimates from the Association of County Commissions and League of Municipalities show that cost would be negligible because the law would only be applied in a very limited, specific cases.

"This would only apply to truly the worst violent offenders so the cost and numbers would be small in comparison to the reward of saving people from potential violent crime," Brown said.

Additionally, this legislation sets a precedent she said could be harmful, as she feels it goes against the principle that the accused are innocent until proven guilty.

“It creates a presumption that release isn’t appropriate, which is contrary to the normal presumption,” Carroll said.

Brown said that because prosecutors must prove that the accused individual is a flight risk or threat to society or themselves, it does not go against the principle of being innocent until proven guilty and also "keeps intact the guaranteed rights under the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution."

Currently, matters of pretrial release are typically left up to a judge who can use his or her discretion. Release on bail can be categorically denied if the individual is charged with a capital felony. Judges can also use their discretion and choose to deny bail if they find that the individual is a flight risk, or “that the defendant’s being at large will pose a real and present danger to others or to the public at large,” according to the Alabama Rules of Criminal Procedure.

Carroll said that denying bail to more people can have negative effects on both the accused individual and society.

“It removes the possibility that that person who is released can return to their community and actually be a good productive member of society,” Carroll said.

There are several studies that have shown that pretrial detention can have negative effects on an individual’s future outcomes. An economic analysis by The Hamilton Project found that individuals held in pretrial detention have an increased likelihood for being convicted and for having future convictions and lower future incomes.

Carroll also said holding individuals before trial keeps them away from their families and communities, where others may depend on them.

While Carroll opposes the legislation, she said she did not want to be insensitive to the pain and trauma of Blanchard’s kidnapping. In fact, she said it’s clear that Aniah’s Law would reduce the risk of similar tragedies in the future, but the policy’s costs need to be considered just as much as any benefits.

“How many people do you hold unnecessarily? How many communities do you tear apart? How many lives do you disrupt in the interest of that possibility that you prevent some future horror from occurring?” she asked.

In general, she’s cautious of legislation that comes in the wake of tragedy. It’s normal for communities to be distressed, she said; it just doesn’t “make good law.”

“Horrific cases generally make for bad legislation because they tend to be reactive, rather than thinking about the systematic impact of whatever the policy is,” she said.

Despite her objections to the legislation, she still expects it will pass, given its overwhelming popular support and the general inclination of Alabama voters.

She expects that if the amendment passes, there will be a federal challenge to the policy based on a possible violation of the Eight Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a claim that Brown thinks is not valid.

Such a challenge would go to a district court and, if the law is overturned there, to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which handles cases from Alabama, Georgia and Florida. She wouldn’t expect the 11th Circuit to uphold a district court overturning it, but similar laws — like ones passed in Arizona — have been overturned in the past.

A law that categorically denied bail to individuals accused of certain sexual offenses was overturned in Arizona in 2017. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case when it was presented to them.

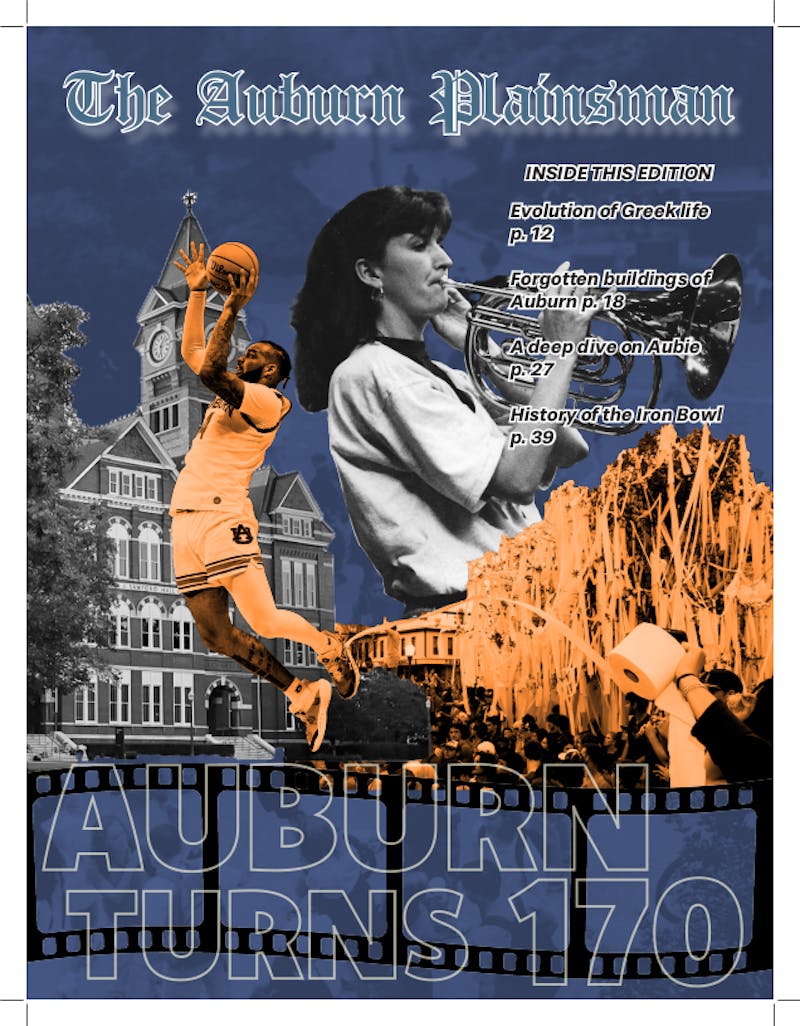

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Evan Mealins, senior in philosophy and economics, is the editor-in-chief of The Auburn Plainsman.