In 1985, on the same day that Bo Jackson received the Heisman Trophy, a federal judge ruled that Alabama must desegregate its colleges. With a Black student population of roughly 3%, Auburn was labeled the most segregated college in the state.

Last fall, only 5% of Auburn students were Black. Since 2007, Black enrollment has been declining, both in terms of percentage and number of people.

In December 2021, the University announced it had received an all-time high in freshman applications for fall 2022 — a 69% increase from fall 2021 and a 155% increase from fall 2020.

Over 40,000 applications were received, with a 76% increase in students applying from Alabama and a 100% increase from students with diverse backgrounds.

Reaching students where they are

“I would say a student from a diverse background would be considered an underrepresented student,” said Joffery Gaymon, Auburn University vice president for enrollment. “That would be an underrepresented geographic location, an underrepresented minority population or socio-economically disadvantaged background.”

Gaymon has been at Auburn in her role since 2019, coordinating the University’s enrollment strategy and directly overseeing the Office of Undergraduate Recruitment, including new student recruitment.

Amid standardized testing sites being limited due to safety concerns during the pandemic, the University began implementing admissions modifications for fall 2021, including joining the Common App.

The Common App is a tool for applicants, teachers, counselors and advisors that seeks to ease the application process by streamlining it, helping to reduce common barriers such as the cost of application fees, which it alleviates through a more efficient fee waiver process.

“It really focuses on access, affordability and breaking down enrollment barriers for students,” Gaymon said. “So, essentially, it’s one application and you have to spend a lot of time doing it, but there’s hundreds of colleges on there. Students make the one application and then select what institution they want to apply to.”

Through Tiger Takeoff, participants could become friends or roommates, alleviating concerns that these students will be entering a new environment alone.

Alongside joining the Common App, Auburn made other modifications to its enrollment strategy, including allowing any valedictorian or salutatorian from an accredited Alabama school to qualify for admission and be accepted to the Honors College.

Additionally, Auburn created a test-optional route to allow students to apply without submitting an ACT or SAT score, reviewing applicants based on leadership activities, letters of recommendation, Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate scores and other factors.

Although Gaymon said there were a lot of people applying through the regular application, the jump in diverse applicants was probably credited to the Common App.

“It really is a tool that’s been proven to help support and strengthen access and affordability and equity,” Gaymon said. “It focuses on access, so there’s a very nice, diverse pool from that, and we just have had very strategic initiatives put in place to build relationships with communities that we may or may not have had in place for the past few years.”

The decision to join the Common App was about taking advantage of being in a space where students already are, Gaymon said.

In that same vein, in underrepresented areas where they struggled to connect with students, the Office of Undergraduate Recruitment works with community organizations that have strong relationships with those students.

“One of them we’ve got a great relationship with right now is the Black Belt Community Foundation,” Gaymon said. “They’re kind of like the hub for the counties in the Black Belt, and we work with them on a number of different initiatives to help. Whether that’s getting admissions material, helping serve as a resource, to promoting scholarships from the area as well.”

Recruitment also works with the Office of Inclusion and Diversity to recruit students. Last year, they collaborated on an event called Tiger Takeoff, an overnight, on-campus experience that takes place right before the admissions application opens.

“A lot of what we see from the admissions process is that a lot of underrepresented students, whether that's by first-generation, by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, come into the process and apply later,” Gaymon said. “They may apply in January, and that’s past the deadline for scholarships, so we decided to have an event that was the earliest in the admissions cycle.”

Giving students resources they need

For students who do not come from communities where attending college is the common or preferred path, applying for and attending a university can be a daunting task.

According to the Center for First-Generation Student Success, 5% of first-generation college students drop out after their first year and do not return again, compared to 1% of continuing-generation students.

These students, whether students of color, low-income or first-generation, often lack the support structures and guidance that universities assume will be provided by family members or mentors. This is one of many factors that contributes to an environment of higher education that is disproportionately wealthy and white.

Adam Harris writes in “The State Must Provide” that higher education has been organized so institutions with the fewest underrepresented students have the most money, highest prestige and best services for students, whether that be at a private or public college.

According to the Center for American Progress, students of color often attend schools that spend less to educate them — more than $1,000 less — than what is spent on their white counterparts.

“This is not by coincidence, but by design,” he writes. “From its inception, the state higher-education system we recognize today was built not on equality, or even an ethos of broad accessibility, but on training a white workforce.”

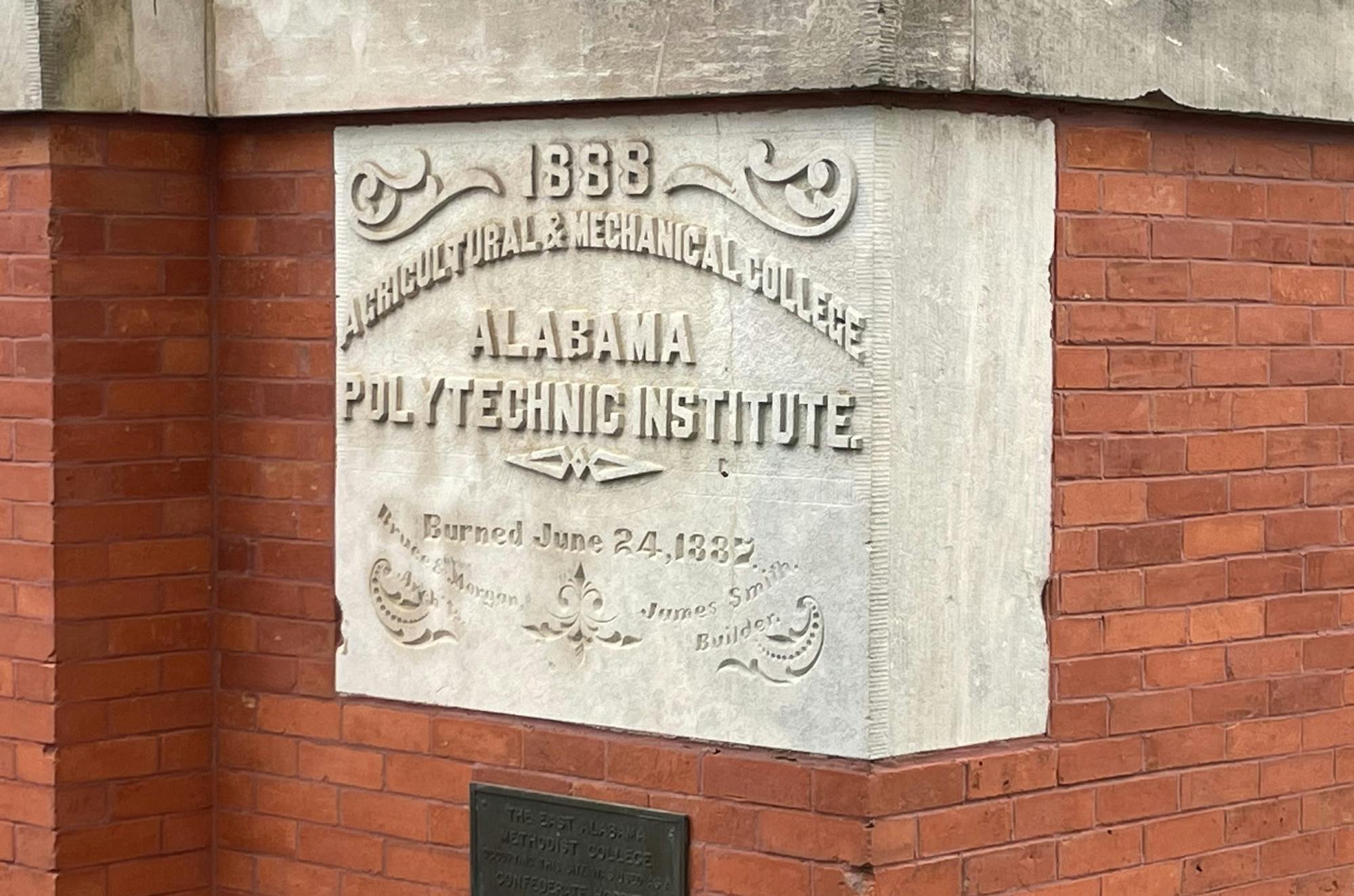

Auburn University first opened its doors in 1859 as a private liberal arts school, then known as East Alabama Male College. After its ownership was transferred to the state in 1872 as a land-grant institution, it became the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama, teaching agriculture, military tactics, mechanical arts and classical studies. It would not see a Black student until 1964.

For universities to fix the inaccessibility that was built into their institutions, they must, in part, provide the resources they expect students to already have, whether that is financial help, community support or other support structures. Through Tiger Takeoff, the Office of Enrollment Management and the Office of Inclusion and Diversity aim to do just that.

Launched last July, Tiger Takeoff brought 89 students from underrepresented backgrounds to Auburn during the summer before their senior year of high school. The goal of the program is similar to that of Camp War Eagle, with some important distinctions, said JuWan Robinson, chief of staff and special assistant at OID.

Camp War Eagle is designed to teach enrolled students the mechanisms to navigate the University: how to use Canvas, how to make a schedule, etc. Tiger Takeoff, on the other hand, aims to prepare soon-to-be applicants for the admissions and, broadly, college experience.

“You’re orienting them to the campus, which is doing it at different points with different information,” Robinson said.

During the program, students were assembled into small groups, each with a “peer leader,” a student who was already attending the University. Throughout the experience, going from events in the schedule and during small group reflection times, peer leaders answered questions students had and shared their own experiences in college. It’s something Robinson said he couldn’t give these students himself.

“Having that near-peer … to tell you, ‘Here’s what this experience has meant to me,’ is a really compelling experience,” Robinson said.

These small groups intellectually prepare students for the college admissions process, but also create a social structure that would follow students into the University if they enroll. These peers could become friends or roommates, alleviating concerns that these students will be entering a new environment alone.

Launched last July, Tiger Takeoff brought 89 students from underrepresented backgrounds to Auburn during the summer before their senior year of high school.

The program seems to have accomplished its goal, Robinson said. Participants said they felt more connected to the University, more prepared for standardized testing and the application process and were more aware of the resources, whether student support or financial, that were available to them.

This, Robinson said, is only half the battle: getting students to view the University as realistically attainable and a place for them is the primary objective of the summer program.

The rest of the battle is making sure students have access to resources and support structures as they continue through college.

During Camp War Eagle, Tiger Takeoff alumni engage with the program again, giving them an opportunity to check-in, look at their class schedules and pair them with a peer mentor who can give a campus tour during the first week.

When these students arrive on campus, they’ll be incorporated into the Tiger Excellence Scholars Program and connected with the Cross Cultural Center for Excellence, where they will be connected with peer leaders and mentors.

“It’s just supporting the system, adjusting the system in a way that instead of relying on students to know they need to do this early, we provide it early,” Robinson said. “We provide it, and we do the outreach, and we work with counselors to get the students to have that experience.”

Share and discuss “To reach underrepresented students, Auburn teaches them to takeoff” on social media.