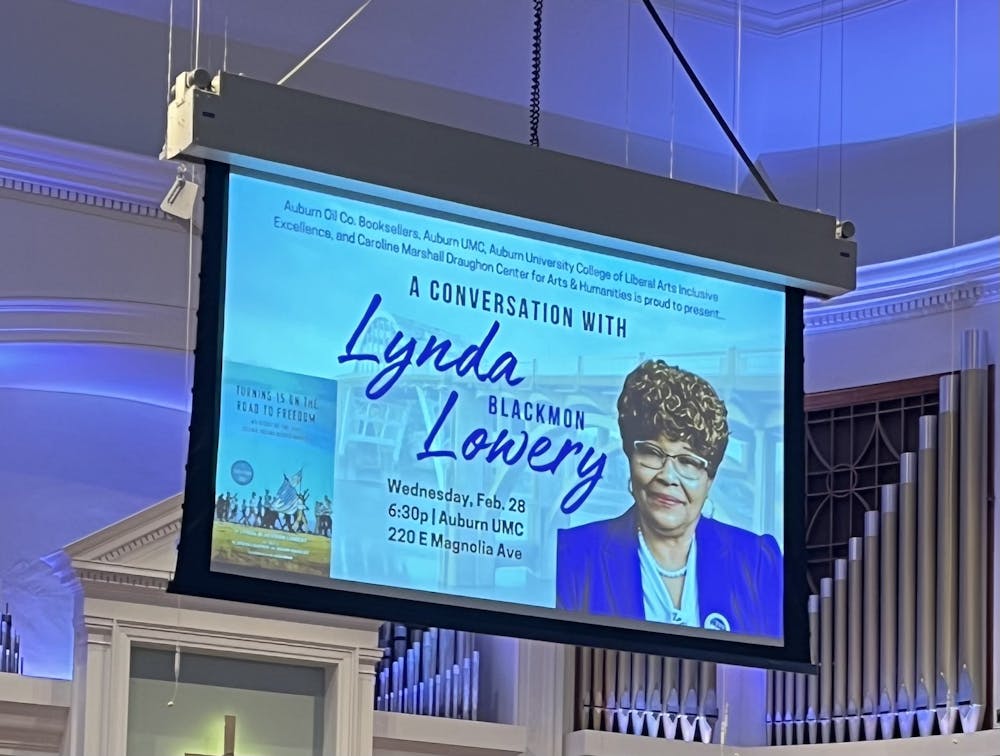

Nearly 60 years ago, Lynda Blackmon Lowery became the youngest person to have marched during Bloody Sunday. Last week, she spoke to the Auburn Family at the Auburn United Methodist Church with the College of Liberal Arts Inclusive Excellence and the Caroline Marshall Draughon Center for the Arts and Humanities sponsoring the lecture.

Lowery, 74, spoke about her experience as she marched on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, at 14 years old and the contents of her memoir, “Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom: My Story of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March.” After the conversation, Lowery held a book signing and Auburn Oil Co. Booksellers gave attendees a chance to buy her book.

The book describes Lowery’s childhood in segregated Selma and recalls Lowery’s experience marching alongside civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. Published in 2015, Lowery’s memoir won a Blue-Ribbon Award from The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books in 2015.

Among the audience was Doris Tolbert Hutchinson, who led a march for Black voting rights in Lee County in 1965. The event leaders chose to also honor those in the Auburn and Lee County communities who fought for civil rights.

Hutchinson, who was an 11th grader when she led the march, wrote a report on the aftermath of the march in The Southern Courier. Her article – “Community Reports” – explained why they were marching, primarily to protest the lack of Black public officials and law enforcement officers, few voter registration days and the “private” signs on the courthouse bathroom doors. Hutchinson got a standing ovation after her name was announced.

Around 70 people marched from Thompson Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church in Opelika to the Lee County Courthouse in Opelika on Sept. 1, 1965. About 66 of the marchers were arrested, 10 of them juveniles.

Rev. Cory Smith welcomed the attendees and led the group in prayer. Joe Davis, director of mission and outreach at Auburn United Methodist Church, then gave remarks and introduced Lowery and Rev. Joan Harrell, who led the conversation with Lowery.

Harrell is a professor in the School of Communication and Journalism at Auburn University and is the director of Inclusive Excellence in the Dean’s Office for the School of Liberal Arts. She is also the founder of the Auburn humanities program, Auburn University Becoming the Beloved Community.

Born in 1950, Lowery grew up in Selma during segregation and the fight for civil rights. Lowery recounted the difference between the Black community and the white community of Selma, with her finding comfort and safety within her neighborhood and community. She described the Black community as fearless and charitable, and preventing themselves from being targets of white violence.

When Lowery was seven years old, her mother died from complications with childbirth, widowing her father and leaving him to care for four children. Her mother needed a blood transfusion but was denied by the white hospital because of her skin color. In her book, Lowery explained that her family and her community knew that if her mother wasn’t Black, she would have been treated at the hospital and would’ve survived.

The blood Lowery’s mom needed was in Birmingham, Alabama, and took 96 hours to arrive by trailway bus. Lowery’s father waited anxiously at the bus station. By the time he could get the blood to the hospital, Lowery’s mother had been dead for 15 minutes.

Those 15 minutes stuck with her father for the rest of his life, Lowery explained. To him, it was his fault that his wife had died. Lowery recalled a time when she was 16 years old and asked her father why he kept repeating the words “15 minutes.”

“You could barely hear, but he'd say, ‘15 minutes.’ One day I asked, ‘What do you mean by 15 minutes?’ And my father started crying, and he said, ‘It was 15 minutes too late,’" Lowery said. “With the blood that could have possibly saved his wife and my mother."

Lowery promised herself that she would make a change.

“So, I made a vow at the age of seven that when I got big, I was going to change things. And nobody would ever have to grow up without a mother again because of the color of skin,” Lowery said.

Lowery described how she relied on her grandmother for strength and guidance after her mother’s death. Lowery credited her grandmother for introducing her to activism. In 1963, Lowery’s grandmother took her to see Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speak about peaceful protests and the rights the Black community deserves.

Lowery’s grandmother brought Lowery and her siblings to a church one night to listen to King speak about Black voter rights. She explained that at first, she didn’t want to listen to him speak, but as soon as he started, she was mesmerized.

“But when Dr. King started to speak, his voice was just soothing and smooth — mesmerizing. I found my 13-year-old self leaning up like everybody else, trying to hear what he was saying. Dr. King was talking to our parents about the right to vote and how they were going to get it nonviolently,” Lowery recalled.

The beginning of Lowery’s activism started with her doing sit-ins at her high school with other students. Before the age of 15, Lowery was arrested nine times for protesting. In her book, Lowery explained the routine of protesting, getting arrested, being released and then protesting again.

After the murder of 26-year-old civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson in 1965, hundreds of civil rights marchers marched 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery to speak with then-Gov. George Wallace. The march consisted of non-violent activists who wanted to demonstrate the right to vote for Black Americans, the need to end segregation and to highlight the racial injustices done to activists like Jackson.

Wallace ordered state troopers to “use whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march.” During his Inaugural Address on Jan. 14, 1963, Wallace declared, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever."

Wallace's efforts to prevent the marchers wasn't the first attempt of his to prevent desegregation. On June 11, 1963, Wallace stood at the steps of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama to block two Black students – James Hood and Vivian Malone – from registering for classes.

Although the students' escort Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach ordered Wallace to step aside, Wallace refused. Instead, Wallace gave a speech on states' rights. It wasn't until President John F. Kennedy authorized the Alabama National Guard to intervene that Wallace moved out of the way.

When Auburn University's first Black student Harold A. Franklin tried to enter campus to enroll for classes on Jan. 4, 1964, he was stopped by state troopers ordered by Wallace. The troopers permitted Franklin to keep going but without the security of Auburn University officials and the FBI.

In the first of three protest marches, around 600 protesters marched out of Selma through U.S. Highway 80 on March 7, 1965. The march remained peaceful until the marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, a bridge in Selma, named after the former state senator, Confederate general and “Grand Dragon” of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan, Edmund Pettus.

Upon crossing the bridge, a wall of state troopers and townspeople blocked the highway. At the very front of the marchers stood 14-year-old Lowery. As the troopers told the activists that their march was illegal and that they must disperse, Lowery felt true fear during a protest for the first time.

The police began to attack the marchers, beating them with clubs and spraying tear gas into the crowds.

As she escaped the troopers and townspeople, Lowery struggled to breathe because of the tear gas and was physically assaulted by a police officer. Lowery sustained injuries to her head, leading to seven stitches above her right eye and 28 stitches on the back of her head.

The attack on peaceful civil rights activists by white officers and townspeople ignited widespread shock and discourse after the assaults were televised across the United States. Among the Black community, the violent reaction toward the protestors lead to the coining of “Bloody Sunday.”

Footage of the rampage aired the night of Bloody Sunday after the film traveled back to ABC’s New York City headquarters. At approximately 9:30 p.m., ABC interrupted their broadcast of the movie “Judgment at Nuremberg,” a dramatized version of the eponymous trials, to broadcast what had occurred earlier that day.

As approximately 48 million Americans tuned in for the show, many viewers were able to make stark comparisons to the oppression of those in the Holocaust and the protestors attacked in Selma. The footage of the police brutality in Selma outraged Americans across the nation, igniting protests nationwide and inspiring others to join the Selma to Montgomery march.

Under the leadership of King, around 2,500 protestors attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge again on March 9, 1965, later called “Turnaround Tuesday.” Again, the protestors were met by state troopers and were forced to turn back. It wasn’t until March 17, 1965, that the protestors could continue to Montgomery after Frank Johnson Jr., a federal district court judge, ruled in the protestors’ favor of exhibiting their right to free speech.

Although injured and traumatized, Lowery and many other protestors marched on toward Montgomery on March 21, 1965. The violence of Bloody Sunday didn’t dissuade them from reaching Gov. Wallace. On March 22, 1965, during the march, Lowery turned 15.

On March 25, 1965, over 25,000 protestors made it to the steps of the Alabama Capitol. Many historians credit the marchers and publicization of Bloody Sunday for swaying public opinion on civil rights and pressuring Congress to protect voting rights for people of color.

Lowery, who still lives in Selma, noted how different the town is compared to her childhood. Since the civil rights movement, Lowery has worked as a case manager for mental health centers. When asked what Black children facing discrimination or racism today should know, Lowery quoted advice her grandmother gave her and her siblings when they were younger.

“I still tell them to believe in themselves, because there's nobody greater walking this earth than you right now. Believe in who you are, and even though all those bricks and stones are going to be thrown at you, be still and believe in you,” Lowery said. “You direct you. And the more you direct you, the more everybody's going to see the beauty inside you. You are important to yourself. If you like yourself, you love yourself. Ain’t nobody gonna take that from you.”

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Michaela Yielding is a senior in journalism currently serving as the news editor. She has been with The Auburn Plainsman since fall 2023.