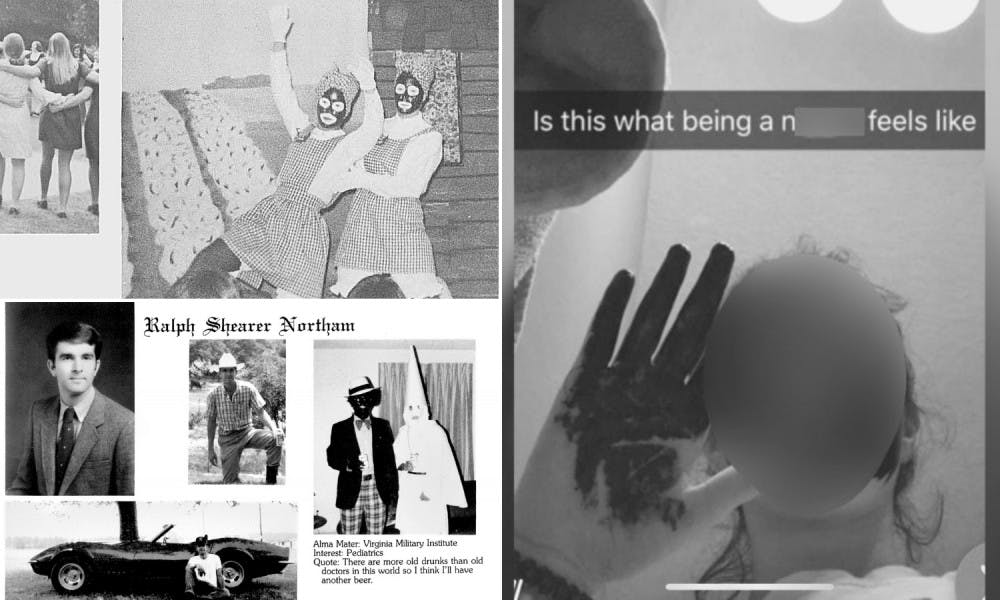

Over the last two weeks, images of students, influencers and elected officials clad in theatrical costumes with black paint plastered on their skin resurfaced with due criticism, but also resounding apologist sentiment.

Auburn did not find itself exempt from the widespread American phenomenon of minstrelsy or blackface.

The Auburn Plainsman recently published two stories detailing Auburn’s intimate relationship with racism and blackface. One concerned a review of Glomeratas, and the other involved an incident with an Auburn High School student.

The found instances of blackface are rooted in the systemic dehumanization and historical caricaturing of black people.

Although The Plainsman found pictures depicting students in blackface in Glomeratas from 1960 to as recently as 1980, blackface continues to plague our community.

Those who put on blackness as a costume during that time submitted to the yearbook almost annually.

In 2001, members of a fraternity wore Ku Klux Klan costumes and posed with a man in blackface wearing a noose in front of a Confederate flag.

In another image, several members of a fraternity wore blackface and wigs to a party.

Both fraternities were suspended.

Last week, an Auburn High School student posted a picture of herself in blackface with the caption, “Is this what being a n----- feels like.”

Each instance speaks to a larger cultural problem that not only demeans the black body and black culture but also national and historical understandings of black people as people.

Austin McCoy, assistant professor of history at Auburn, spoke to the damaging nature of blackface, describing its historical groundings in minstrel shows.

“Blackface was about making black folks not seem real and therefore making it easier for other white Americans to discriminate or even inflict violence against black people,” McCoy told The Plainsman.

The act of wearing another human being as a costume separates the race being worn from their personhood. That makes it easier to dismiss their oppression as mere fable.

These mindsets seep into our collective American consciousness, causing the ideology to pass from one generation to the next.

Alabama’s history is inextricable from racism and violence toward the black community. Perhaps, racism’s distinct Alabama-ness is the reason why so many who call the state home are afraid to call these actions what they are — overtly and blatantly racist, then and now.

A number of people who commented on our Facebook and Twitter about our pieces argued the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s were a different time — that we should not judge those in that time by today’s moral standards. They said we should “move on.”

That mindset is dangerous. With racism obviously still with us today, it’s imperative that we remember our history and recognize where we went wrong. And we have to do that without qualifiers like, “It was a different time.”

Yes, it was a different time. The difference was that racism was acceptable. Just because something was socially acceptable, doesn’t make it not racist.

Other things, like lynching and Jim Crow segregation, were not only socially acceptable, but they were law. That doesn’t make them any less immoral or any less racist.

The truth is that blackface and minstrelsy were racist in the 1800s when the practice was a staple of popular culture.

The truth is that blackface and minstrelsy were racist in the 1900s when black people finally had a platform and the right, in some places, to speak out against it.

The truth is that blackface and minstrelsy were racist in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s when white people chose to continue the practice despite frequent and vocal criticism.

And the truth is that it remains racist.

If we can’t recognize, accept and reflect upon the full reality of our past, how are we to correct our present and better our future?

Remnants of our violent, racist past linger with us today. They are not gone. The racism of today is generally more subtle. It is words spoken behind closed doors, sentences prefaced with, “I have a black friend” or “I am not racist, but,” and through empty apologies and denial.

Today’s racism is perpetuated by way of willful ignorance.

Blackface is not an innocent mistake. It wasn’t a cute attempt at mimicking popular black artists, no matter the intent.

It is a conscious choice to manipulate the black body and don stereotypical or exaggerated images of blackness.

The formulation of caricatures of black people through minstrelsy existed for the sole purpose of dehumanization and socioeconomic and political suppression.

That history cannot be separated from blackface and minstrelsy today or even a few decades ago.

Alabama cannot distance itself from its past. Alabama and Auburn must confront our shortcomings head on.

No longer can an environment exist where any person deems it permissible to wear blackface.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

The opinions of The Auburn Plainsman staff are restricted to these pages.

This editorial is the majority opinion of the Editorial Board and is the official opinion of the newspaper.

The opinions expressed in columns and letters represent the views and opinions of their individual authors.

These opinions do not necessarily reflect the Auburn University student body, faculty, administration or Board of Trustees.

The Auburn Plainsman welcomes letters from students, as well as faculty, administrators, alumni and those not affiliated with the University.