Lila Quintero Weaver is a graphic novelist and author born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She moved to Marion, Alabama at the age of 5. Artwork from her graphic novel “Darkroom: Memoirs in Black in White” will be on display at the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Arts through March 30.

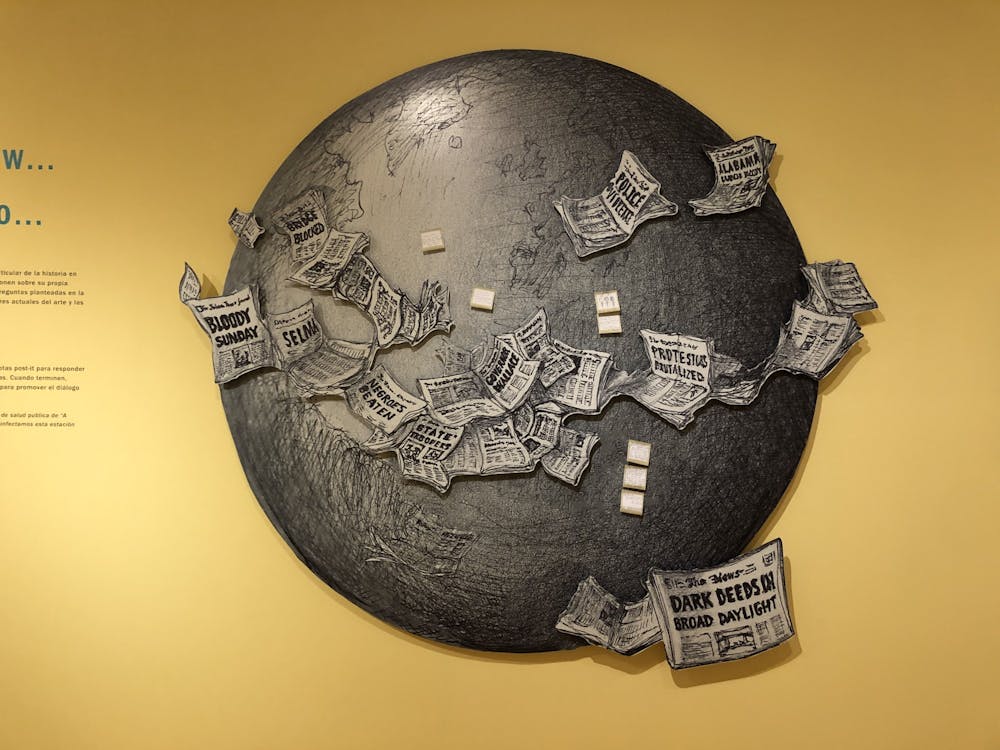

The museum will display 25 pieces of artwork and personal objects from the graphic novel which takes place during the civil rights era and includes Weaver's experiences as an immigrant in the South.

Weaver said the title of the novel “Darkroom” is significant as it connects the civil rights movement to her own upbringing.

“It's called 'darkroom' because, at the most concrete level, there is this connection with photography because my dad, sort of as a sideline, did photography," Weaver said. "He had a makeshift darkroom in the house. I was fascinated by the whole process of how photos are taken, how you take a photo then run it through the enlarger, the role of light and the chemical baths that you put into all that, to me was really fascinating, even as a child because you got to see this image forming on the page, almost almost as if by magic.”

Her father's interest in photography also played a role in the graphic novel, she said. Although her dad was not a photojournalist, she connected his photography to the historical significance that photographs had at the time of the civil rights movement.

The subtitle of the novel, “Memoirs in Black and White” represents the main color scheme of the book but also the political setting of the book. Weaver stated that her family felt like they did not fit into the current conversation of race-related issues.

“You also have sort of a play on words with this issue of race being very, very central,” Weaver said. “And as Latinos, we were entering a demographic that was either black or white and then we came in, kind of not very well defined. You know, what are we? Who are we? Which box do we check? So, that’s how it all comes together.”

According to Weaver, her childhood was not like that of her friends, and growing up in America, specifically Alabama, affected her own connection with her Argentinian heritage.

“I would say my upbringing was very different from my peers in Alabama,” Weaver said. “I think it's more challenging if the family immigrated to a part of the U.S. that is not highly diverse. If there were a lot of Latinas or people from distinct cultures that maybe would have softened the sense of being oddballs and curiosities.”

Weaver immigrated to the United States only speaking Spanish, she said. Shortly after learning to speak English, she no longer had an interest in speaking her native language in her bilingual household.

While Weaver felt like an outsider growing up, she now realizes that she shared many commonalities with other children in similar situations.

“I've found that that happens to a lot of immigrant kids when they go to a different culture,” Weaver said. “I would say I grew up like a lot of immigrant kids grow up, which is sort of a push pull between the culture that the parents embrace and maybe want to continue to honor and celebrate. Whereas the children a lot of times don't want to do that. They resist it for a number of reasons. So, that was a big factor in my growing up.”

As a child, Weaver had very traditional parents who she stated feared certain forms of Americanism such as consumerism culture.

“We grew up without television because they did not approve of TV,” Weaver said. "They thought that it was a waste of time, that [it] would make you sort of become mentally lazy. And maybe, maybe they even thought it would expose us to bad moral influences. It was just one of those things we hated because everybody around us had a TV and watched whatever the great shows were.”

In retrospect, this gave her the opportunity to indulge in more creative ventures such as reading and writing, she said. Her parents would have never envisioned their daughter to one day grow up and write a story about their lives, but she credits her parents' focus on education and art for her interest in creating.

Weaver is also a children's author and wrote a book titled “My Year in the Middle,” a semi autobiographical book which centers around a young immigrant in Alabama and her challenges surrounding race and societal pressures of middle school.

Having written both a traditional book and graphic novel, Weaver described the differences in constructing the two forms of media.

“Putting together a graphic novel, writing and illustrating is a huge labor,” Weaver said. “I'm not saying that writing a novel is not huge labor, also, but having done it in the sequence of writing the graphic memoir first and then the traditional model, it really felt so much easier. Of course, you know, there's all of the standard challenges and struggles related to writing, but producing around 500 drawings, what I had to do for Darkroom, that took me years. There's no comparison as far as the work. But, it seems like it almost sort of sits in a different part of the brain.”

Because of the pandemic and her distance from Auburn, Weaver has yet to see her exhibit in person but she hopes to see it soon.

“It's been great working with [the museum]. They're very impressive,” Weaver said. “We have been talking about this exhibit now for [what] feels like a couple of years and that may not be an exaggeration. So, it's been a long time coming. I can't wait to see and it's such an honor to be invited to do it.”

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

My Ly, junior in journalism, is the community editor of The Auburn Plainsman.