Recently, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled in an 8-1 decision that videos, recordings of 911 calls, photos, autopsy records, emails and texts are related to investigative materials and don’t have to be released to the public.

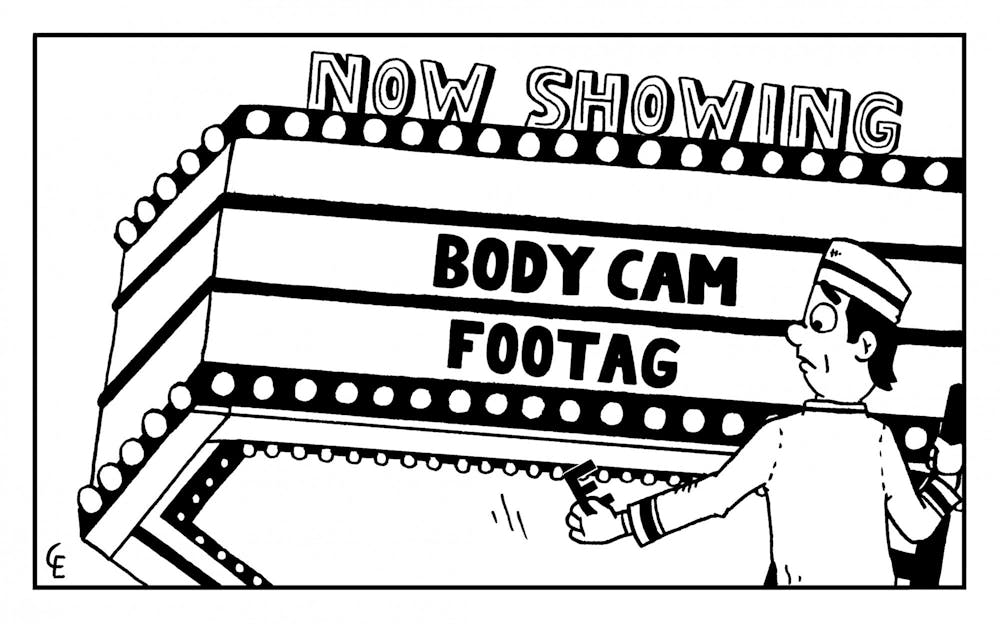

This ruling is the result of a lawsuit filed by Lagniappe, a weekly paper in Mobile, against Baldwin County Sheriff Huey Mack and his office. Lagniappe alleged that the office violated the Open Records Act — which grants citizens the right to inspect and copy public records — by failing to produce body camera footage and other records relating to a police-involved shooting.

In 2017, a deputy sheriff responded to the scene of a single-vehicle accident, where he fatally shot and killed the driver.

The Baldwin County Major Crimes Unit investigated the circumstances of the shooting, but ultimately a grand jury declined to indict on any criminal charge. The incident was captured through both the sheriff’s body cam and the phones of eyewitnesses.

Mack, the Baldwin County sheriff, said in an interview he believed that there is information that should be released to the public but a balance should be found to protect investigations.

While there should be a certain degree of protection that should be considered in an ongoing investigation, as well as the rights of the defendants to a fair trial, there are several problems with this ruling.

In this case, the sheriff’s office rejected Lagniappe's request under the “investigative-privilege statute” which says “law enforcement investigative reports and related investigative material are not public records."

The investigative privilege statute doesn’t specify if an investigation must be open for the materials in that investigation to be exempt from the Open Records Act.

But in Jan. 2019, when a reporter for the Lagniappe requested the materials related to the case, there wasn't an investigation to protect.

Ultimately, the particulars of this case don't matter as much as the ruling.

Chief Justice Tom Parker, the lone dissent to the ruling, wrote that "the [Open Records Act] exists to compel people to do what they will not do voluntarily."

Before this decision, those advocating for the public interest could at least negotiate with law enforcement to get a portion of an investigative file, according to J. Evans Bailey, an attorney for the Alabama Press Association, in an interview with AL.com.

Now, they have little to no negotiating power.

Alabama police and prosecutors have a history of withholding body camera footage, only releasing it when it paints their officers in a positive light or after public protests.

In 2018, the Alabama Attorney General released footage of the E.J Bradford shooting at a mall in Hoover, only after protests in the streets.

Last year, police called a press conference in Decatur, after a video showing an officer punching a liquor store owner began circulating on social media. They showed reporters an edited clip of bodycam footage.

Body cameras can at once be a part of investigative material and public records. Body cameras are paid for by the public, with taxpayer money, to document the work of an entity that serves the public.

Body cameras belong to the public.

The only exception for body camera footage to be withheld if it has been requested is to protect the identity of a civilian in an ongoing investigation.

In July, the Auburn City Council unanimously approved a $1.5 million contract with Axon Enterprise spanning over five years to supply APD with new technology — including body cams, and vehicle cameras that send live footage to the police headquarters and a virtual reality training system. The City Council budget will be able to absorb about $300,000 of the annual cost of the contract, but in the end all of it is funded by taxpayers.

It is not only a waste of money to have body cameras with no guarantee we'd see the footage that we pay for, but it severely diminishes the degree to which police officers can be held accountable.

The functions of body camera footage are transparency and accountability. The public wants to know what law enforcement is doing when there's no one around, no one to monitor their behavior except for the cameras on their chest.

A study by George Mason University found that citizens do feel safer when police have cameras on, but how safe can they feel knowing that the information could be withheld because it is "investigative material,” even if there is no investigation?

Additionally, what if law enforcement decides to release the footage, but edit out some parts in order to "protect" an investigation? The full story in some cases, could never really be known and justice could never really be served.

This ruling infringes on the legal rights of Alabamians, as Chief Justice Parker wrote.

The only way to reform this ruling now is by strengthening the Open Records Act, something that has been tried and has failed repeatedly in the past. Bailey, the Alabama Press Association attorney, said it depends on people now to raise awareness — we need to demand transparency, and for public records to stay public.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Editorials represent the majority view of The Plainsman's editorial board and do not necessarily represent that of the entire newsroom.