The University's efforts to identify the foot soldiers of the Bloody Sunday march in Selma turn towards the public as professors Richard Burt and Keith Hebert’s Bloody Sunday Passion Project reaches social media with the engagement of Honors College students.

The ongoing project has recently established an online Facebook page where the community and general public can easily access information and questions regarding the project. The Facebook page regularly publishes pictures, content and updates asking for the public’s help in identifying the Bloody Sunday marchers.

Richard Burt, the McWhorter Endowed Chair and head of the McWhorter School of Building Science, shares the story and vision behind the Facebook page.

“We compiled a rudimentary list of people we think marched and gave that list to the students to contact the individuals involved," Burt said. "Then we thought, ‘Let's try social media.’ So, we set up the Facebook page and that has been getting a lot of traction."

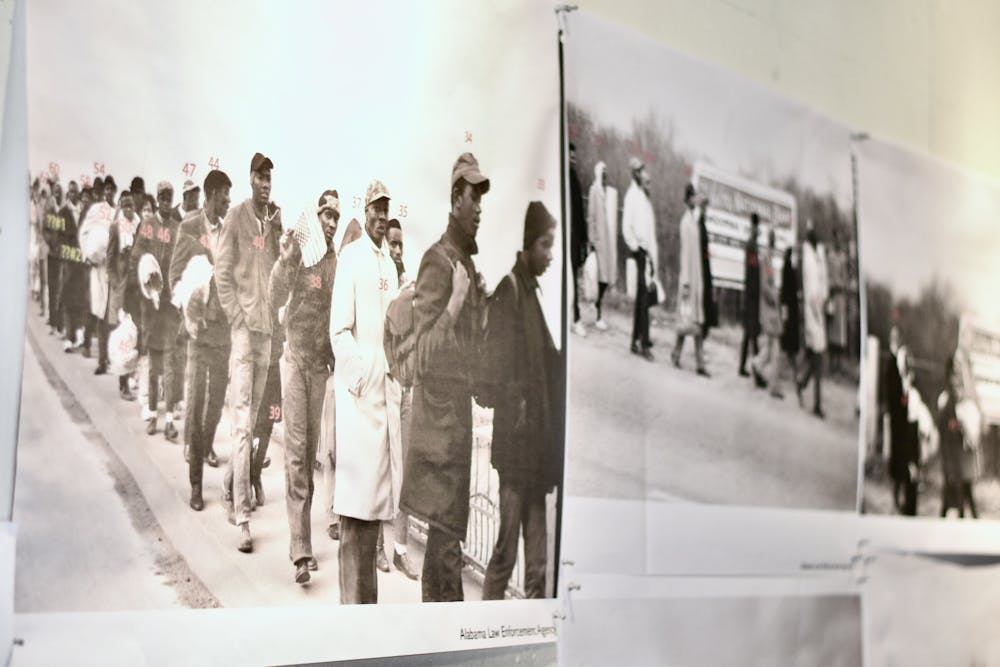

The project initially began in 2015 when Burt, along with a team of researchers, began harnessing new technology such as digital photogrammetry to analyze a series of pictures and film clips taken on Bloody Sunday. As they began piecing the map together, Burt said he asked for the list of Bloody Sunday marchers to give them names, not just numbers.

“We found out pretty soon that there wasn’t a list," Burt said. "That’s a big hole in history.”

This hole in history has consistently been highlighted by Burt, Keith Hebert, Honors College students and the Selma community. Since partnering with Hebert and launching the Honors Bloody Sunday class and Facebook page, the project has now successfully identified upwards of 60 marchers.

The students are gaining hands-on experience with historical data, innovative technology, social media feedback and conversations with Bloody Sunday marchers as they continue to unveil the identities of each marcher. A small group of students were able to travel to Selma on Oct. 1 to meet with marchers.

Valerie Weaver, sophomore in history, noted how her involvement with the project and traveling to Selma has shaped her college experience.

“We tend to think of these events as so far away, but there are living, breathing people that experienced these tragedies,” Weaver said. “Getting to hear their stories makes me all the more grateful for the world we have today. I realize that we often take it for granted. I cannot pretend to know what they went through, but I can do my best to understand it and how it shaped them.”

A number of students share this perspective on the project, namely that it has helped them try to understand the lasting impact of the march.

Jack Bell, sophomore in history, shares his experience working on the project.

“I had the opportunity to meet Joanne Bland — a foot soldier on the Bloody Sunday march — in person,” Bell said. “Hearing her experience was powerful, and it gave valuable first-hand perspective about the fight for civil rights. Reading accounts of the march and seeing pictures from Bloody Sunday are useful, but visiting the city itself — even 56 years later — is valuable when piecing together the events from that day and identifying those involved.”

Bloody Sunday occurred on March 7, 1965, in Selma, Alabama, amidst the increasing racial tensions of the civil rights movement and the fight for equal voting rights.

Led by activist leaders John Lewis and Hosea Williams, a group of nearly 600 peaceful protestors gathered on a Sunday morning. They then began their march through downtown Selma with hopes of reaching the state capital in Montgomery.

Although the grounds of the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery would not be covered, what took place on the grounds just past the Edmund Pettus Bridge was a landmark moment in civil rights history. Additionally, it was an impetus for the country to increasingly advocate for the voices and rights of African-Americans, according to Martin Luther King Jr.

As the protestors neared the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in downtown Selma, they were met on the other side by state troopers, policemen and white spectators. The protestors finished their march over the Alabama River as they were attacked by the line of law enforcement officers yielding clubs, whips and barbed wire.

Weaver expressed her belief in the importance of Bloody Sunday and the timeliness of the project.

“This is such an important part of history that changed the country, and it has just been brushed over time and time again,” Weaver said. “I’m so glad we are finally getting to give these people the credit they deserve.”

The project has set up an exhibition space in the college of architecture, design and construction in Dudley Hall where professors and students have compiled pictures and identifications of the marchers. The space is open to the public, and Burt highly encourages students to visit the space.

“I think history, when it is reported, usually only focuses on the nationally-known people and the leaders of the movement,” Burt said. “But what the students are starting to realize is that a large number of the marchers were high school kids, young high school kids. They were a part of the community.”

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.