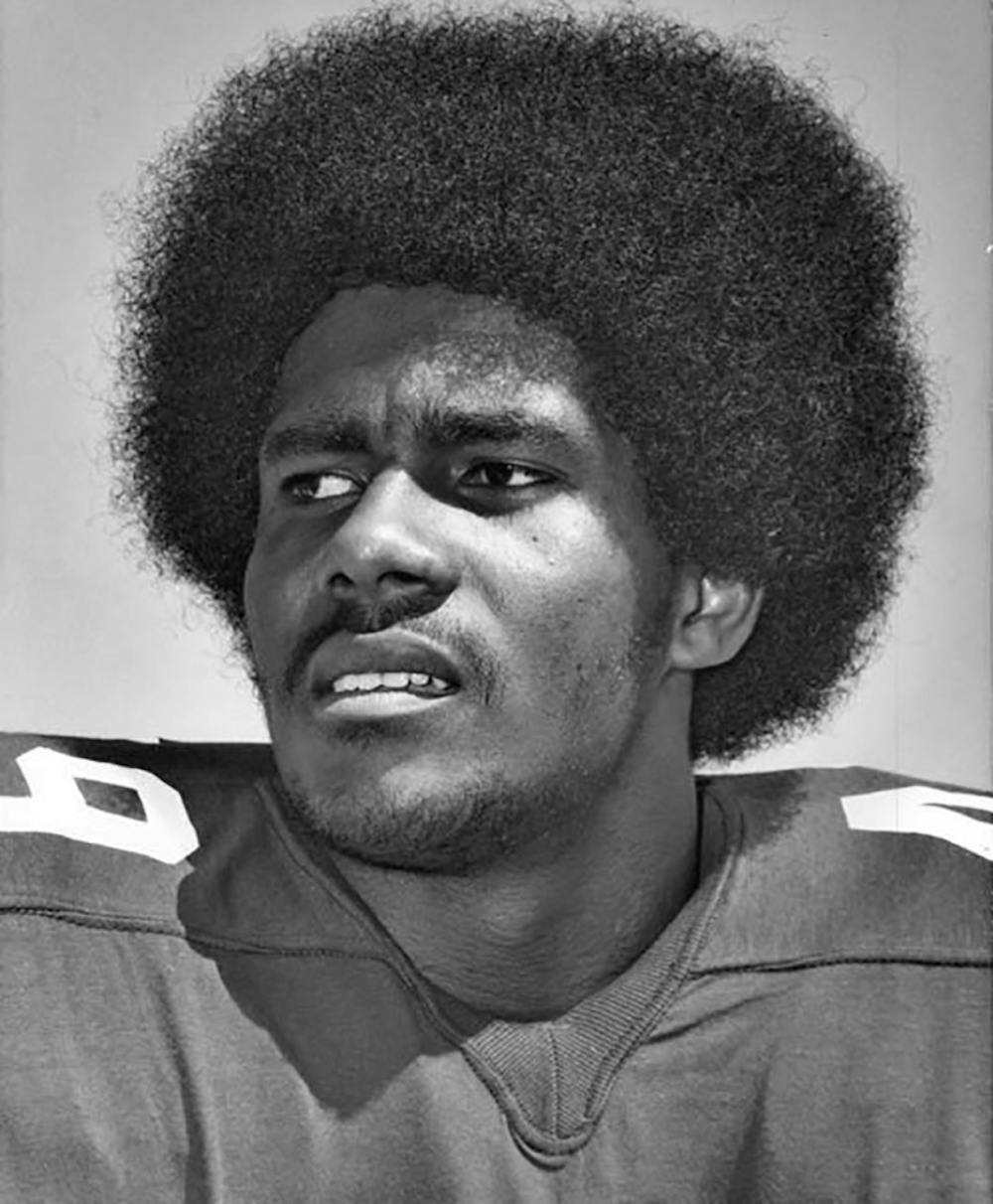

Thom Gossom stepped onto the green grass in the Auburn football stadium, looking at the confederate flag waving in the air above. He knew the difference he and other black student athletes would make in Auburn Athletics.

In 1970, there was only one black athlete at Auburn University. Gossom was the second. As the first black athlete to walk across the stage at graduation, Gossom made sure to inspire the men who came after him to graduate.

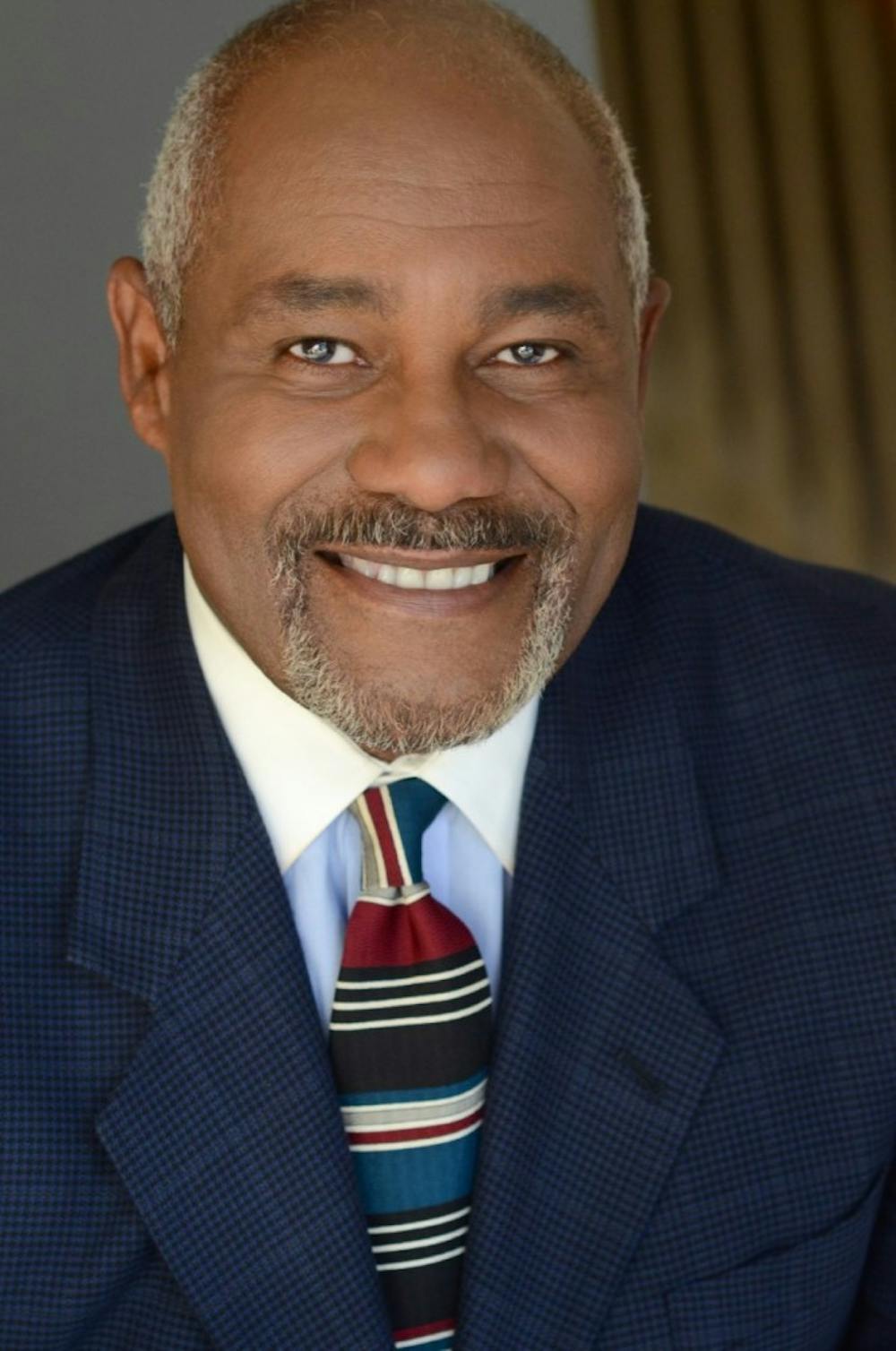

Because of this legacy, Gossom received the Alumni Lifetime Achievement Award on March 2, 2019.

“The phone call came out of the blue,” Gossom said.

His time at Auburn started in 1970, only six years after the University desegregated. He graduated in 1975.

“It makes me proud,” Gossom said. “I think we were very aware in terms of our place in history. What we were doing was trying to make a difference.”

Putting on the uniform wasn’t just for pride. It was to show a difference and to stand up for the black men and women that would come after Gossom and his fellow African-American athletes at the time.

“To be as young as we were, we were very aware of the situation,” Gossom said. “I think we were very aware of where we were in terms of our place at the University, in terms in our place in history and that what we were doing was trying to make a difference not only for those who came behind us, but for kids who wanted to dream, that they could do what we were doing.”

Gossom’s place on the Auburn football team, along with the first black player James Owens, was historic. He knew his duty and legacy would stem from more than just how he did on the field.

“Athletes that I admired were athletes that were socially conscious, who participated in the civil rights activities, so that’s where I thought I could make a difference,” he said.

Gossom started playing football his junior year at John Carroll High School in Birmingham. He had attended Catholic school for most of his grade school years.

He was one of a few black athletes to start playing at the high school.

“I basically integrated the athletic program there,” Gossom said. “I ended up having a great experience there, but there were negative things. There were schools that wouldn’t let me play in their gym.”

Gossom was called numerous racial slurs then, but they didn’t stop him.

He learned to deal with racism on the football field in high school — it was something he was used to off the field, anyway. When he got to Auburn, the experience was different for him. He already faced adversity and racism in high school football, so it made it easier to bear, he said.

Gossom came to Auburn for academics, walking onto the football team in 1970. He experienced a different side of Auburn Athletics for his first year, as walk-ons had a different locker room and didn’t receive jersey numbers.

As only the second black man on the team, Gossom knew the impact his presence would have on the future of the program.

It wasn’t until the summer after his first year that Gossom was awarded a scholarship for football and made the transition to the student athlete side.

Being an Auburn Tiger was something Gossom was always proud of, but looking back, he knows there were institutional problems within the University.

“I would hear my teammates use the n-word just as much as the other teams did,” Gossom said. “Flying the confederate flag over the stadium while we played games was embarrassing. It was something that, you know, if you tried to take it on head on and complain, who were you going to complain to?”

Their coach cared, but Gossom said he didn’t think the man was ready for those kinds of talks just yet. The South was still getting used to proper integration into white institutions.

Today, the men are family, and all have evolved into more socially conscious individuals, Gossom said. In his three years on the team, they never lost a home game.

“We played some good football, and we watched the integration come in,” Gossom said.

However, he felt isolated from white students in some ways while attending as black students were basically in another world in this small town.

“There was no diversity amongst the black kids,” Gossom said. “The social life was bad. We would have great games, win the game, but there was nowhere to go after the game. So, we just kind of went back to the dorm and hung out.”

There was an extra dorm room they turned into their own club, Gossom said, laughing. It housed parties with only black men and women, though. There were only a handful of them, and they all knew each other.

“Being an athlete helped because athletes were treated different and treated a little more special,” he said. “It was trying, but I think we know what we were there for.”

His love of the game was important to Gossom, but graduation was his ultimate goal and his biggest accomplishment.

“My last year, there were three of us on the team,” Gossom said. “By the end of that decade, the black athlete wasn’t the majority, but they were certainly populating the team. I was proud to be the first (black) athlete to graduate.”

Gossom wanted to see more of his black teammates graduate like he did.

He knew football was not in everyone’s future, and he wanted them to have a good foundation and take advantage of the education they were being offered.

“I made sure that they all graduated — every black guy who came there under my watch when I was the oldest athlete graduated from Auburn – and I was very, very proud of that as well,” Gossom said.

After graduating with a degree in communication, Gossom moved back to Birmingham where he said he was a part of “the first black things” to come to the city.

He was the first black athlete in the Quarterback Club and took part in an integrated theater company, which started the trajectory of his next great life adventure.

Gossom participated in theater performances in Birmingham for the next four to five years and was voted the city’s favorite actor in a local poll.

Eventually, the right person saw his theatrical work, and he received a phone call from an agent in Los Angeles interested in casting him in a movie.

“I got a reputation for being a good actor,” Gossom said. “I didn’t do my first play until I was 31 years old.”

He eventually moved to Los Angeles for 15 years and starred in movies like “Miss Evers’ Boys” and “Fight Club” and television shows like “NYPD Blue” and “In the Heat of the Night.”

Gossom continues his work as an actor, and leads his consulting firm Best Gurl Inc. alongside his wife, Joyce Gillie Gossom.

He has served as chair of the Auburn University Foundation Board from 2015 to 2016, the first black man in the position, and is a director on the Auburn Research and Technology Foundation. He was also head of the Billion Dollar Campaign.

Gossom continues to stay involved with the University because he loves the institution and working with young people, he said. More importantly, he wants the University to be on the correct side of progress throughout history.

“Auburn has this thing where we don’t talk about things like that,” he said. “We sort of duck our heads in the sand. You have to own your history, and that’s what I’ve always said.”

He brings the University’s past mistakes up to help it move forward, he said.

“You don’t get to do that unless you own it,” Gossom said. “Then, we can move forward to the progress we need to make as individuals, as human beings and as a university.”

“I’ve always had a commitment to working with the University to move it down the road so that white students, Chinese students, Latin students, whoever, could feel comfortable there and have pride that this was [their place] as well,” he said.

People don’t change, Gossom said. Instead, they evolve. He admits even he has evolved into a better man from when he was on the team.

The University must evolve, too, he said, and it was up to the administration to properly confront problems of inequality.

“We’ve got a lot of ground to cover,” he said.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Mikayla Burns, senior in journalism and Spanish, is managing editor of The Auburn Plainsman.