Prince Michael Sammons finds strength through God and comfort in family.

Sammons, an offensive lineman for the Auburn Tigers and native of Nigeria, received his American citizenship earlier this semester.

It was a long process for Sammons to get to America, but it was even longer for him to gain his citizenship.

In order to obtain citizenship, you must be a permanent resident of the U.S. for at least five years, complete an application, attend an interview and pass an English and a civics test, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Sammons said he is no stranger to hard work and had a lot of support in studying for and taking the test.

“My mom says, ‘If it is God’s willing for it to happen, it will,’” he said.

This statement has carried Sammons more than 6,000 miles away from his home of Lagos, Nigeria to Auburn, Alabama. At the age of 15, he left Africa to pursue a better life through basketball and ended up a linebacker for the Auburn Tigers.

“We grew up financially not strong,” Sammons said. “We managed.”

He grew up in a small, one-bedroom house, with just enough room for a bed, a TV, a couch and a sleeping area for him and his brothers. However, that didn’t stop his mother from instilling positivity, hard work and generosity in him and his eight siblings.

While his brothers found jobs, he grew up playing soccer.

“I didn’t want to get a job. I wanted to play sports,” Sammons said. “That’s the gift God gave to me.”

At one particular soccer tournament, the stakes were high for Sammons.

The winning team would take home a cash prize.

It was enough to feed his family for “a long time,” he said, enough for his mother to be at ease for a few weeks.

But Sammons’ team lost.

He wept when the final whistle blew. It wasn’t the actual loss that drove him to tears — it was knowing he had failed his chance to feed his family. He was only 12 years old.

As he walked off the field, a stranger that Sammons now calls his “guardian angel” approached him.

“What’s wrong with you?” Sammons recalled the man asking him.

He told the man his story. The man counted some of the award money and handed it to Sammons.

“I can’t take it,” he recalled saying.

“Take it,” the man told him.

Sammons accepted it and thanked him. The man suggested he play basketball.

“God opened a door for you to bless your family,” the man told Sammons.

So Sammons went to the courts.

He said he wasn’t good at first and didn’t know how to dribble or shoot, much to the amusement of those on the court.

“Girls are laughing at me; boys are laughing at me,” Sammons said. “But that doesn’t stop me, because I never give up.”

Six months later, after instruction from a coach and member of the basketball team, he was invited to travel and play with a team. After one game, another stranger came up to him to offer a scholarship — but only if he could dunk the ball.

“I kind of paused a minute,” Sammons said. “I said, ‘You’ll give me a scholarship if I can dunk?’ And he says ‘I’ll give you a scholarship right now if you can dunk.’”

That night, he stayed up trying to dunk. But as much as he tried, he couldn’t do it.

“When I went home, my friends were hyping me up, and they said all you gotta do is go up, jump higher and dunk the ball,” Sammons said.

The next day, he did just that.

“I was so happy — I was expecting the scholarship to come to me right away, in that moment, but it didn’t,” Sammons said. “I go home to tell my mom the whole story, and she was just laughing at me and says, ‘One thing about you, you don’t give up.”

She told him that if it’s God’s willing, it’ll happen. And it did.

Two weeks later, Sammons got a call from an American asking if he had a passport because a school in Maryland was offering him a scholarship for basketball.

He said his family didn’t have enough money for an international passport, so he dropped out of school to start working odd jobs and helping his mother at her fruit stand, in order to save up enough money.

One day, Sammons said a woman saw him working and told him to go back to school so that he could be someone and make money in the future.

Later, he said the same woman came back and bought the entire fruit stand, giving him enough money for a passport: the key to receiving his scholarship.

Weeks later, a stranger came to his house and gave him an envelope.

The contents promised four years of school in America. All he had to do was get his visa.

After getting through tedious requirements and paperwork, Sammons was finally handed it at the U.S. embassy.

He was so afraid of losing the visa, he said, so afraid of the dream disappearing, that when he gripped the envelope in his hands he left the building as quickly as he could, thinking they might say it was a mistake.

Soon after leaving the building, Sammons received a call from his brother, who told him to come home.

His mother was in critical condition.

When he finally got back, his mother had already passed away.

He laid right beside her.

“I didn’t know when you died, you get so cold,” he said. “I just put a blanket over her.”

With the death of his mother, his original plan began to crumble. A basketball coach from Wisconsin, however, agreed to pay for his flight to America and housed him until he found a school to attend.

A few months later, he learned his father had died back home in Nigeria. By that time, Sammons had been out of school for a year, but he finally found a school and basketball program that would accept him.

Betsy and Brandon Sammons, who taught at Cincinnati Hills Christian Academy, decided to legally adopt Sammons. He had a home and was finally attending an American school.

Once there, Sammons said both the football and basketball coaches were clamoring to get him on either the field or the court.

However, he didn’t even know what football was. He spent the first year on the team as their water boy.

As Sammons picked up on the game and began playing, a number of colleges started offering him scholarships.

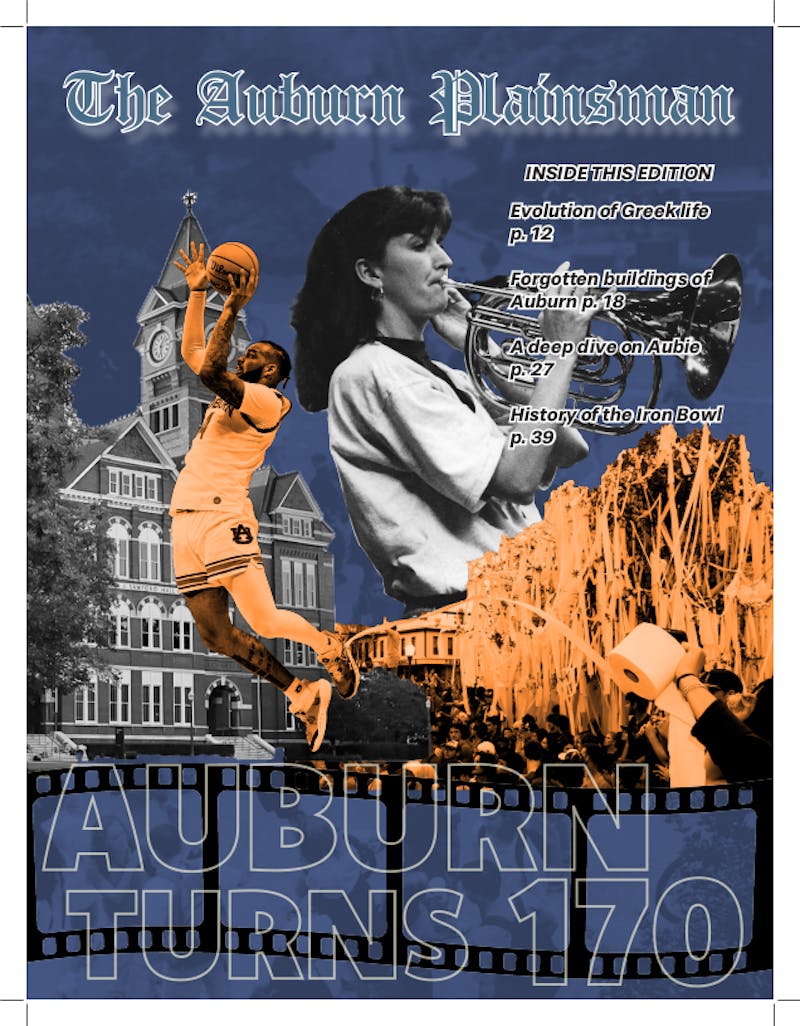

Prince Michael Sammons at the Auburn vs Georgia game on Saturday, Nov. 11 in Auburn, Ala.

“All of a sudden, Auburn offered me a scholarship, like two days before signing day,” Sammons said. “So I took an official visit, and when I came, [Prince Tega Wanogho], who I used to play basketball with in Africa, said, ‘Hey, this school would really be a good fit for you.’”

Sammons said he felt a family starting to build around him at Auburn. It’s the real reason he chose Auburn.

“Having someone from the same place I’m from kind of helped, and so that’s why I came here,” he said.

Even though football allowed him to be here, and even while having hopes of playing in the NFL, Sammons said it’s all second to his education.

“I truly wanted to come here to get a better education, so I could become a role model to my brothers,” Sammons said.

In the future, he wants to work for a non-profit business so he can help people and give back to his country. Getting his citizenship was just one step in the process.

“I was trying to seize me being here permanently ... so that I would have the privilege to stay here ... and become someone in life,” he said.

Sammons said he is ready to continue his journey in the states.

And as his mother used to say, if it’s Gods willing, he said, he will become someone and use his gifts for good.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.